As an emerging scholar, it is with some trepidation that I describe emerging or “vital” areas of research in my field; I do not have the perspective that some of my senior colleagues might possess. Nor is the field on behalf of which I might speak immediately apparent to me. A product of my time, all of my training has been interdisciplinary, and in this I am far from unique among scholars who research dance. The field of dance studies, as might be said of any field, is constituted through the mutual recognition of those who participate in it. It is the gravitational pull of recognition that ultimately grounds me within dance studies, even as my interests in media technologies situate me as a satellite in relation to its orbit. I would like to focus this thought piece, therefore, on analyses of the digital and digital modes of analysis arising from within and in relation to the field of dance studies.

Dance scholars carry their practices with them ... it is not a given that dance studies is a humanities field.

From the outset, I want to distinguish digital research in dance studies, which is an emerging area of inquiry, from the long-established field of dance-technology. Each represents different intellectual genealogies, political and philosophical investments, and motivating questions. While I think a rapprochement is on the horizon, it would be misleading to collapse the two.

Dance-technology grew out of artistic experimentations with interactive technologies, especially motion sensing, tracking, and capturing tools, and has been an important site for the development of computational systems alongside choreographic research. It has, of late, also begun to advance a dance-based philosophy of mind. Arising principally from research based in physical practices, attuned to choreographic processes, and resulting primarily in artistic or hybrid aesthetic-scholastic works, its research areas tend to emphasize making dance knowledge and choreographic thinking visible through partnerships with cognitive researchers and data scientists. Due to differences in government funding structures and the presence (or absence) of dance in the academy, Western Europe, Canada, and Australia have proven more hospitable to the long-term development of dance-technology, whereas dance studies, in which I am locating emerging modes of digital research, has historically been dominated by scholars trained in the United States.

The field of dance studies is also rooted in practices of dancing. However, scholars draw upon research methods from history and anthropology, combined with analytical frames and additional approaches from cultural studies and critical theory. Its research areas therefore emphasize critically framed historical and cultural analyses of dance and movement practices. A multi-disciplinary field, dance studies is greatly informed by scholars’ travels among theater and performance studies, folklore and ethnomusicology, popular culture and media studies, ethnic and area studies, gender and sexuality studies, political theory, economics, and corporeality studies. Moving among these fields and finding co-articulations around shared concepts of performance, improvisation, and embodiment, for example, and mobilizing concepts such as choreography1 and kinesthesia2 beyond the field of dance proper, scholars have extended the reach of dance studies from dancers, dances, and dancing to include all sorts of human and non-human movements and movers. Generally, however, analyses of movement in dance studies intersect with analyses of bodily techniques3 and increasingly employ some form of choreographic analysis.4 In contradistinction to movement analysis,5 choreographic analysis regards choreography as dispositif, that is to say, as a matrix of relations that is both the enabling and the constraining condition of possibility for performance.

Nonetheless, the tethering of physical practice to scholarly product in practice-informed research6 has always energized dance studies, which has made a virtue out of an institutional necessity. Dance is not like music, visual art, or literature, where colleges and universities segregate historians and cultural critics from creative practitioners, housing them in separate programs, departments, or even schools.7 Instead, dance scholars carry their practices with them. As a result, it is not a given that dance studies is a humanities field. It is only very recently that dance scholarship has been included within its embrace–so recently, in fact, that a series of summer seminars and post-doctoral fellowships inaugurated in 2012 under the banner “Dance Studies in/and the Humanities”8 gave scholars in dance studies reason to take stock of what has shifted across the performing arts such that some in the field would identify with the humanities rather than with the arts. Indeed, some dance scholars may legitimately wonder whether this new designation precludes their participation. Yet the shifting boundaries of the humanities, which have enabled dance studies to be located within their milieu, have also opened the humanities to alternative research objects and practices, such as those found in the digital humanities. Valuing collaborative and creative research, new forms of humanistic inquiry connect to and validate the artistic undercurrent of contemporary dance scholarship, which is experiencing an unprecedented expansion in tandem with an explosion of dance documentation.

Archivization, Documentation, and the Digital

From my perspective, limited documentation, and limited access to what documentation exists, has been the core impediment to dance scholarship.9 Although dancers and dance scholars have labored intensively to articulate alternative value systems, in a culture of knowledge that valorizes disembodied archival records, dance practices have been dispossessed of their histories.10 The absence of documentation has presented a greater barrier to the legitimacy of dance as an academic field of study than, for example, puritanical fears of the body, the steady decline of physical and arts education arts in primary and secondary school curricula, or institutionalized discrimination (dance being a field dominated by women and racial and sexual minorities). Though writing, film/video, and other technologies of memory have assisted in the transfer of dance knowledge across geographical distances and temporal gaps, the principal, and arguably most expedient, means of transmitting dances has always been from dancing body to dancing body. Oral traditions and notation systems of various sorts have bolstered the foundational mimetic scenario of dance education, which includes more than the simple translation of movement from one body to another: to learn a dance style or a set choreography, one needs to participate in a dancing community, which entails epistemological and ethical infrastructures. Dancers and dance practices have generally been intertwined, with dancers implicated in the perpetuation of practices by carrying the layered histories of movement in their bodies, both as personal biography and as communal choreography. Not only skill, then, but also lineage has been important to a dancer’s overall valuation. Fluent observers seek out family resemblances in movement styles that evidence training within a certain school or community, usually with distinct regional variations. In this economy of movement, eyewitness accounts and first-person narratives, for example by dance critics, anthropologists, and creative practitioners themselves, formed the basis for dance scholarship.

For those of us who produce or conduct research in the areas of dance, movement, and gesture, [digitized video documentation] is our "Gutenberg."

Times have changed. Thanks to the ubiquity of digital technologies, from consumer-grade electronics to high-end professional gear, dance is experiencing a digitization boom for which there is no historical precedent. Libraries and other institutions have begun digitizing their holdings and making them available online.11 Artists are partnering with academic and government institutions to take control of their own archives, curating their careers for online viewers.12 Arts presenters and cultural curators are collaborating with artists to present high-quality video available for streaming or download.13 Artists are utilizing digital tools to analyze their own work, and even the work of other artists, in artist-driven dance-technology projects.14 Dance camps and competitions produce promotional videos to attract new participants and audiences, and tutorials breaking down the latest popular dance styles abound. Clips from dance television programs past and present circulate online, and decades of music videos are now accessible on Vevo. Meanwhile, dancers at home and in their backyards, on school grounds and public plazas, in streets and in clubs, in coffee shops and shopping malls, post their dances on YouTube and Facebook. Dance practices have always been on the move, and no amount of analysis will be able to account for the sheer variety of scenarios in which dancing appears–sometimes in a passing gesture or an accidental syncopated step. With increased access to video documentation, however, dance studies can attend to more aspects of dance’s movements across bodies, across populations and geographic distances, and across media technologies and devices.

The impact of this unleashing of documentation could not be more profound. It has reshaped how choreographers source and generate movement material, fueling contemporary artists’ turn to the archive for inspiration and re-interpretation.15 It has altered the landscape of available gestures for both conceptual and popular artists, who find vast treasure troves of “found choreography” in social media sites. It has fundamentally changed the teaching of dance history, which once relied on photographs and grainy bootleg videos. And it has shifted the possibilities (and demands) for contemporary dance studies with the formulation and development of digital research projects. Let me be clear: for those of us who produce or conduct research in the areas of dance, movement, and gesture, this is our “Gutenberg.”

Digital Research in Dance Studies

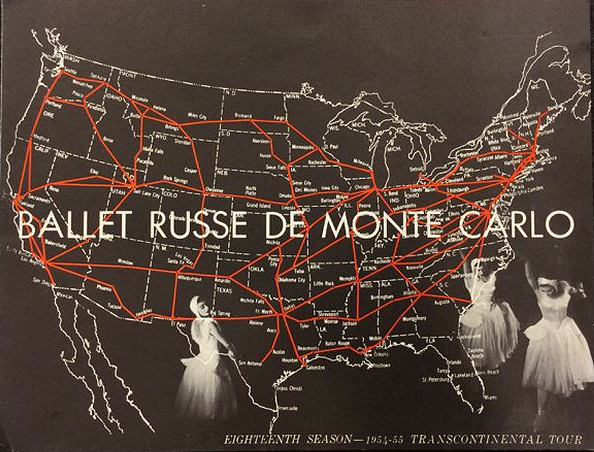

We are already seeing how dance practitioners take up digital technologies, fueling innovation in tandem with documentation. Following such developments, scholars’ research trajectories increasingly demand that they grapple with digital media, regardless of whether or not they are versed in contemporary media studies or critical analyses of digital cultures. Some scholars are additionally finding that the tools of digital analysis are opening previously laborious or impossible avenues of research. Principal vectors in this cluster of interests include archeologies of media technologies and systems of dance documentation; visualizing networks of influence and support and geographically mapping the locations and trajectories of dancers and dance companies; and investigations into the cultural politics of dance practices’ digitally enabled global circulations. Some projects leverage tools and techniques from the digital humanities to translate analogue artifacts and relationships into born-digital works of scholarship. Some are more concerned with digital sociality and, therefore, digital objects, but oriented toward questions of cultural fluency, the ethics of embodiment, and the movement of political and social bodies.

For example, a research project I am spearheading, called Mapping Touring, is tracking the domestic and international touring of early 20th-century dance artists and companies to better grasp the intercultural influences embedded in artists’ movement aesthetics.16 In order for this project to be possible, and in anticipation of future research, we are creating a database of information culled from performance programs, including dates and locations of performance, venues, and the repertory performed, among other details, all of which will be openly available to other researchers. Kate Elswit’s ongoing Moving Bodies, Moving Culture project currently leverages the Stanford Humanities Lab visualization tool Palladio to consider duration, location, distance, and the passage of time as she considers infrastructures that support dance’s circulation.17 Focusing on dance impresario Sol Hurok, Elswit brings private patronage structures to the forefront of her analysis as a way to contemplate dance’s transnational movements. A consortium of university investigators, dance artists, and advocates are developing The Dance Cloud (working title), a digital commons dedicated to equipping dance artists with strategies and resources to sustain their dance careers.18 This research “hub” will enable user-driven sharing by dance artists, researchers, and intermediaries at all stages of the career continuum. Using various publication and social networking templates, the Cloud will encourage cross-cultural, multi-generational debate on issues of dance labor, infrastructure, and support for working artists.

Like many dance-trained researchers who spend any amount of time in archives, VK Preston meditates on the kinesthetic imaginary that complements working through the traces of dances past. As an early modernist working with 17th-century dance texts, their 19th-century reproductions, and 21st-century digital copies, Preston additionally considers what it feels like to move among differently mediated versions, each reflecting the representational priorities of their respective eras, each offering different sights and textures from which to animate dance history.19 Hannah Kosstrin has recently worked with LabanWriter programmer David Ralley to develop the Labanotation iPad app KineScribe.20 Kosstrin considers what impact print and digital media have on this form of dance notation as an embodied research practice, particularly in its generative rather than purely documentary capacities. She is also interested in exploring the ways that Labanotation, video documentation, and written annotation can exist alongside each other in productive and mutually informative projects of dance analysis. Paul Scolieri is similarly beginning to explore the possibilities of annotating moving images, working in partnership with the New York Public Library.

The abovementioned projects highlight explorations into the use of digital tools, particularly in conversation with the digital humanities, to produce analyses that are valuable for dance studies. Analyses of digital objects are no less important, however, and scholars engaged in such research, some of whom are noted above, have questioned the right of access and challenge the will to knowledge attending technologies of capture and display. Key in this type of work is a critique of embodiment, which describes both the fact of human-being as being-body and the process of incorporating and storing sensory and kinesthetic information in one’s body. Embodiment cannot be taken as the disinterested ground of physical practice–even sensation has a politics.21 Indeed, debates regarding the cultural politics of embodiment have persisted in dance studies for quite some time, articulated alongside revised genealogies of performance initiated by Brenda Dixon Gottschild’s ground-breaking Africanist readings of works in ballet choreographer George Balanchine’s oeuvre.22 Such re-readings of dance’s embodied archives and their physical artifacts have rewritten the histories of concert and social dance forms alike, troubling the ease with which white choreographers, performers, and social dancers took up movement vocabularies as a natural resource that, if mixed with their own labor, could unproblematically become their own.23 Social media have now opened access to global databases of artistic, popular, and folk gestures and accelerated their rates of transfer across populations and domains. The cultivation of global citizenship is increasingly becoming a question of corporeal cosmopolitanism, tipping these analyses from the politics of representation to the ethics of embodiment.

Anthea Kraut, for example, has extensively researched the ways in which “stealing steps” both promoted the growth of tap dance as a form and fueled interracial tensions when originators were not credited.24 Kraut considers the ways in which dancers and choreographers have tried to protect themselves against unauthorized replications of movements, steps, gestures, or entire choreographed works, highlighting the raced, gendered, and classed dimensions of homage and appropriation, of copyright and plagiarism, of cultural/intellectual property and theft. She joins a number of other scholars, including Thomas F. DeFrantz,25 in thinking through the implications of dance forms’ unfettered circulations beyond the communities and cultural logics that give movement meaning, as well as their transformations into empty gestural commodities. Alex Harlig takes a slightly different approach, suggesting that communities of practice continue to organize themselves in online spaces, where, moreover, they make visible the stakes of policing the boundaries of the very movement practices that they are generating.26 Moving oral traditions to YouTube comments, these communities collectively author dance histories through committed acts of fandom.

From the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge to “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot,” internet memes and the gestures of social movements also fall under the umbrella of digital research in dance studies. Calling upon viewers to document themselves embodying these and other choreographies, and to add them to an online archive of many other such gestures, participatory culture is adding new movement vocabularies to collective action. But as Anusha Kedhar and others have shown with “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot,” general calls for participation do not differentiate between victims and allies or suggest how different roles might be supported with distinct choreographies.27 Expressing solidarity through embodying a choreography that does not reflect one’s lived experience–raising one’s hands in surrender while fearing for one’s life, for example–can actually erase the victims of the very injustices that the gesture gestures toward.28

Sitting inside dance studies, all of the research agendas I have sketched out maintain connections among historical, cultural, and critical dimensions. Indeed, I would argue that it is the necessary simultaneity of these dimensions in the production of critical cultural histories of movement that locates this research within dance studies–even as these projects necessarily also draw from other areas of inquiry. Dance studies is gradually coming to terms with contemporary realities of how dances, movements, and gestures travel through technologies of capture and transmission, as well as the choreographies of collectivity that manifest when movements are re/materialized across bodies and populations. Sooner rather than later, the field will also have to grapple with digital research as a modality not limited to “creative research,” but as a vital part of humanities scholars’ historical and interpretive work, regardless of the medium(s) in which that work takes final form.

Digital Humanities, Dance-Technology, and Digital Dance Studies

In their mutual turn toward computation, both the digital humanities and dance-technology have forged productive alliances with the sciences and with scientific modes of research. This shared orientation toward computing and computational analysis, however, has opened a curious and unexpected gap between the arts and humanities at the site of digital research. I propose that digital dance studies can help close this gap in its deployment of analytical tools and strategies developed in the digital humanities and dance-technology, while bringing forward the values and intellectual investments of dance studies.

The digital humanities have produced a number of exciting approaches to research. Digital humanists have partnered with libraries in mass digitization efforts, scanning innumerable codices, still images, films, diaries, correspondence, and other media in an effort to make the contents of physical archival collections more accessible to more people. Reflecting an ethic of making within the humanities, digital humanists have also created tools with which to analyze, model, and display digital objects. Omeka, Scalar, HyperCities, and Palladio are just a few tools intended to lower the barrier for scholars who want to engage in digital research without first having to master a suite of programming languages. Other tools of analysis, from the user-friendly Google Maps to the professional-grade data analysis system Tableau, are also productively deployed toward humanistic ends. The power of these tools lies in their flexibility and adaptability to many different kinds of analytical approaches.

Dance-technology, meanwhile, has emerged with analytical tools of its own that are designed for motion.29 Like the digital humanities, dance-technology has historically had a very high barrier to entry. As a result, early work in this domain reflected the idiosyncratic interests and computational abilities of its practitioners, resulting in spectacular but unrepeatable endeavors. This field, however, has also begun to create software programs that anticipate the needs of dance scholars who may or may not also be dance artists. In particular, Motion Bank’s video annotation software in development PM2GO30 is an exciting tool for a wide range of performing arts researchers. With it, scholars can analyze the structures underlying a performance, whether those are choreographic or, for example, a playscript or musical score, along with individual performers’ interpretations of that guiding structure. PM2GO is built to enable analysis of multiple performers and the causation or correlation of their actions, but because it is a video annotation tool, it can support the analysis of any moving image, from the latest music video to ethnographic field research, from whatever perspective a researcher might bring.

Using analytical tools developed in fields such as the digital humanities and dance-technology, digital dance studies can additionally bring forward the values that have been articulated in dance studies, whether such projects are built around key individuals, dance styles, physical techniques, networks of affiliation, canonical works, unwritten histories, etc. I have already stated that I believe the intellectual priorities of dance studies to be in the production of critical cultural histories of movement (and/or critical histories of movement cultures), but I have yet to describe how dance studies manifests core values in scholarship, which is to say, in writing.

That dance scholars value physical practice, coupled with the difficulties of representing moving bodies on the printed page, has resulted in the emergence of writing styles that attempt to write from the body31 in crafting sensuous, visceral prose that tracks dynamism, rhythmic structure, and phrasing, the tickle of intimate vulnerability and the rush of collectivity, the tense stillness of breathless anticipation and the glorious tedium of unrelenting virtuosity–translating the viewer’s/author’s own bodily experiences into a new performance for readers. Scholars from many fields proclaim an interest in corporeality, but few writers are able to grasp the fleshy viscosity of somaticity.32 Many prefer arid styles of writing to more humid prose, lest the acknowledgement of the bodily mediation of all apprehension lead them down the dark, sticky corridor of solipsism. Although not every dance scholar identifies as a dancer and not all dance writing is somatic or performative, cumulatively, scholarly texts in dance studies are textured by practices of dancing.

If digital humanities and dance-technology offer possible methodological approaches to digital dance scholarship, opening up new avenues for dance analysis, dance studies provides its political stakes and especially its written vocabularies, which have been cultivated and crafted over many years by many voices engaging in the arduous and poetic work of translating movement into words. The position of dance studies in the performing arts allows it to retain a substantive connection to corporeality, the aesthetics of movement, and physical and sensory knowledge, while its emergence as a humanities field validates the critical scholarship that has formed in relation to physical practice. The digital research emerging within dance studies capitalizes on this ambiguity, bridging a gap introduced between the arts and the humanities in the wake of the computational turn.

Although I designate digital dance studies as a vital area of inquiry, it is not my hope for it to emerge as a subfield, contributing to a contemporary trend toward area-fication within dance studies. This trend risks isolating scholars and researchers as they pursue greater intellectual depth and academic rigor in narrowing areas of expertise. Yet it is precisely the proximity of multidisciplinary approaches, the messiness and misunderstandings that attend such proximity, and the labor of translation across disciplinary and methodological differences, that hold dance scholars accountable to each other in the production of critical cultural histories of movement. My wish for digital research in dance studies is that analyses of the digital and digital modes of analysis will flourish across all domains of dance studies, supporting the multidisciplinary study of dance.

References

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977 (1972). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. 2008. “The Enduring Ephemeral, or the Future Is a Memory.” Critical Inquiry 35 (Autumn): 148–171.

The Dance Cloud. University of California, Los Angeles; Wesleyan; and The Ohio State University. Web.

DeFrantz, Thomas F. 2012. “Unchecked Popularity: Neoliberal Circulations of Black Social Dance.” In Neoliberalism and Global Theatres: Performance Permutations. Edited by Lara D. Nielsen and Patricia Ybarra. London: Palgrave.

Eiko and Koma. 2015. Eiko & Koma. Web. Accessed 15 April 2015.

Elswit, Kate. Moving Bodies, Moving Culture: The Work of Impresario Sol Hurok. Web. Accessed 15 April 2015.

The Forsythe Company. 2010–2013. Motion Bank. Web. Accessed 15 April 2015.

Foster, Susan Leigh. 1998. “Choreographies of Gender.” Signs 24, 1 (Autumn): 1–33.

Foster, Susan Leigh. 2003. “Choreographies of Protest.” Theatre Journal 55 (3): 395–412.

Foucault, Michel. 1995 (1975). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Salan Sheridan. New York, Vintage Books.

George-Graves, Nadine. 2009. “‘Just Like Being at the Zoo’: Primitivity and Ragtime Dance.” In Ballroom, Boogie, Shimmy Sham, Shake: A Social and Popular Dance Reader. Edited by Julie Malnig. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Gottschild, Brenda Dixon. 1998. Digging the Africanist Presence in American Performance: Dance and Other Contexts. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Greco, Emio. 2007. Capturing Intention. ICKamsterdam and Amsterdam School of the Arts. Web/multimedia. Accessed 15 April 2015.

Harlig, Alex. 2015. “Not Grammar Police but Genre Police: YouTube Comments as Art Criticism.” PCA/ACA conference paper.

Hartman, Saidiya V. 1997. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kedhar, Anusha. 2014. “‘Hands Up! Don’t Shoot!’: Gesture, Choreography, and Protest in Ferguson.” The Feminist Wire. 6 October 2014.

Kosstrin, Hannah, and David Ralley. 2014. Kinescribe. Portand, OR: Reed College. iPad app.

Kraut, Anthea. 2010. “Stealing Steps and Signature Moves: Embodied Theories of Dance as Intellectual Property.” Theatre Journal 62 (2): 173–189.

Martin, Randy. 1998. Critical Moves: Dance Studies in Theory and Politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mauss, Marcel. 1973. “Techniques of the Body.” Economy and Society 2 (1): 70–88.

Miller, Bebe. 2015. Dance Fort: A History. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University, iBook.

Murphy, Jacqueline Shea. 2007. The People Have Never Stopped Dancing: Native American Modern Dance Histories. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Pew Center for Arts and Heritage. 2015. A Steady Pulse: Restaging Lucinda Childs, 1963–78. Web. Accessed 15 April 2015.

Preston, V. K. 2015. “‘How Do I Touch This Text?’ Or, The Interdisciplines Between: Dance and Theater in Early Modern Archives.” In The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Theater. Edited by Nadine George-Graves. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rancière, Jacques. 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics. Edited and translated by Gabriel Rockhill. London: Continuum.

Srinivasan, Priya. 2012. Sweating Saris: Indian Dance as Transnational Labor. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

- See, especially, Susan Leigh Foster, “Choreographies of Gender,” Signs 24.1 (Autumn 1998): 1-33. See also Foster, “Choreographies of Protest,” Theatre Journal 55.3 (2003): 395-412. ↩

- See Randy Martin, Critical Moves: Dance Studies in Theory and Politics, Durham: Duke UP, 1998. ↩

- See, for instance, Marcel Mauss, “Techniques of the Body,” Economy and Society 2.1 (1973): 70-88; Michel Foucault (1975), Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan, NY: Vintage Books, 1995; Pierre Bourdieu (1972), Outline of a Theory of Practice, trans. Richard Nice, Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1977. ↩

- In the past two decades, “choreography,” which referred specifically to the act of writing dances before it came to mean a repeatable sequence of steps and gestures, has expanded immeasurably in scope. Following in the wake of dance and movement practices’ continuously shifting sites–circulating among stage and screen, club and street, and outdoor plazas and museums–as an analytical principle, choreography can describe any patterned, governed, or directed movement. This has the additional benefit of relieving scholars of the obligation of determining whether or not their objects of analysis are dance because the already shaky myth of artistic autonomy is unsustainable when considering movement practices outside the concert dance canon, where, meanwhile, artistic experimentations have irrevocably blurred the boundaries between dance and non-dance. ↩

- Movement analysis typically refers to Laban Movement Analysis, which provides a specialized language for describing qualities of motion and the physical effort with which movements are executed, among other dimensions. Movement analysis also appears in exercise and sports sciences as the biomechanical study of neuro-muscular pathways in human movement. Choreographic analysis does not attend to the anatomical, physiological, or kinesiological aspects of movement from a scientific perspective but may include these, along with sensation, entrainment, affect, etc., from a socio-cultural perspective. ↩

- I choose the term practice-informed very specifically to differentiate it from what is often called practice-led, practice-based, or practice-as-research, which is a model of dance research coming out of the U.K. ↩

- It seems noteworthy here that dance found its first academic home not among the arts but in women’s physical education programs. ↩

- “Dance Studies in/and the Humanities” is supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and is led by Susan Manning (Northwestern), Janice Ross (Stanford), and Rebecca Schneider (Brown). ↩

- I argue this even as I do not lament ephemerality as many other scholars of dance and performance have. Nor, I wish to note, should digital technologies be considered a remedy for dance’s disappearance. Both dance practices and digital technologies exist in what Wendy Chun has described as the “enduring ephemeral.” See Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, “The Enduring Ephemeral, or the Future is a Memory,” Critical Inquiry 35 (Autumn 2008): 148-171. ↩

- Unremarkably, the effects of this dispossession are unevenly distributed, evoking histories of colonization and resistance. ↩

- For example, the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library, Jacob’s Pillow, the Smithsonian, and the Library of Congress, among others, have made moving image material available online in whole or in part. ↩

- For a particularly rich example of a Web-based artist-driven archive, see Siobhan Davies Replay: The Archive of Siobhan Davies Dance, Coventry University, 2009, web, 15 Apr. 2015. Eiko and Koma have integrated their moving and still image archive, along with reviews, essays, and event announcements, directly into their website. See Eiko & Koma, web, 15 Apr. 2015. For examples of more intimate treatments of Lucinda Childs’s early choreographic career and Bebe Miller’s auto-archiving work for stage A History, see, respectively, A Steady Pulse: Restaging Lucinda Childs, 1963-78, The Pew Center for Arts and Heritage, 2015, web, 15 Apr. 2015; and Dance Fort: A History, The Ohio State University, 2015, iBook. ↩

- See, for example, Ontheboards.tv, a project of Seattle’s On the Boards theater, and the performing arts online streaming service 2ndline.tv. ↩

- Most notable among these are Motion Bank, The Forsythe Company, 2010-2013, web, 15 Apr. 2015, and Emio Greco|PC, Capturing Intention, ICKamsterdam & Amsterdam School of the Arts, 2007, multiple media. ↩

- This turn is itself fueled by the timing of an entire generation of dance, movement, and performance artists taking stock of their careers in retrospectives. ↩

- Blog posts detailing the progress of this project can be found at www.harmonybench.com. ↩

- Kate Elswit, Moving Bodies, Moving Culture: The Work of Impresario Sol Hurok, web, 15 Apr. 2015. Using digital analytical tools to support written scholarship rather than as a form of output in its own right, Elswit demonstrates the transformative possibilities of multi-modal thinking and digital modeling in dance studies. For more information, see https://movingbodiesmovingculture.wordpress.com/ ↩

- The Dance Cloud is comprised of researchers from UCLA, Wesleyan, and The Ohio State University, along with field partners from non-university dance organizations and dance companies. For more information, contact Project Coordinator Sarah Wilbur at s (dot) wilbur (at) ucla (dot) edu. ↩

- See VK Preston, “‘How do I touch this text?’ Or, The Interdisciplines Between: Dance and Theater in Early Modern Archives,” The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Theater, ed. Nadine George-Graves, New York: Oxford UP, forthcoming 2015. ↩

- Hannah Kosstrin and David Ralley, Kinescribe, Reed College, 2014, iPad app. For news and other updates about this project, go to www.kinescribe.org. ↩

- See Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics, trans. Gabriel Rockhill, London: Continuum, 2004. ↩

- See Brenda Dixon Gottschild, Digging the Africanist Presence in American Performance: Dance and other Contexts, Westport: Praeger, 1998. ↩

- See, especially, Jacqueline Shea Murphy, The People Have Never Stopped Dancing: Native American Modern Dance Histories, Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2007; Priya Srinivasan, Sweating Saris: Indian Dance as Transnational Labor, Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2012; Nadine George-Graves, “‘Just Like Being at the Zoo’: Primitivity and Ragtime Dance,” Ballroom, Boogie, Shimmy Sham, Shake: A Social and Popular Dance Reader, ed. Julie Malnig, Urbana: U of Illinois P, 2009. ↩

- Anthea Kraut, “Stealing Steps and Signature Moves: Embodied Theories of Dance as Intellectual Property,” Theatre Journal 62.2 (2010): 173-189. ↩

- Thomas F. DeFrantz, “Unchecked Popularity: Neoliberal Circulations of Black Social Dance,” Neoliberalism and Global Theatres: Performance Permutations, ed. Lara D. Nielsen and Patricia Ybarra, London: Palgrave, 2012. ↩

- Alex Harlig, “Not Grammar Police but Genre Police: YouTube Comments as Art Criticism,” PCA/ACA, April 2015, conference paper. ↩

- Anusha Kedhar, “‘Hands Up! Don’t Shoot!’: Gesture, Choreography, and Protest in Ferguson,” The Feminist Wire, 6 Oct. 2014, web, 20 April 2015. ↩

- For an excellent reading of the problematics around white empathy in relation to black suffering, see Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America, New York: Oxford UP, 1997. ↩

- Other video analysis programs are available, but these tend to emphasize ways of analyzing motion for the purpose of improving performance within sports contexts rather than facilitating comparative and interpretive possibilities in social or artistic contexts. ↩

- PM2GO is an update of Piecemaker, which was a software specific to The Forsythe Company’s choreography and rehearsal processes. ↩

- This style of writing is as informed by French feminism and ethnographic “thick description” as it is by dance. ↩

- Laura U. Marks, Kathleen Stewart, C. Nadia Seremetakis, and Avery Gordon are a few such writers whom I admire. ↩