1. Feminist Temporalities

This paper explores some current contexts of ‘feminist articulation’ in a globalised and media-saturated world. I track some of the changing fates of feminist discourse within and outside the academy in Europe (particularly the UK), with a focus on generational tensions, the relationship between sexuality and gender, and the subject of feminism. A particular concern for me here is the commensurability between an increased take-up of ‘feminism’ in media and cultural contexts, as well as within new social movements across Europe, and the particularly unequal burden of austerity politics that women are expected to carry. My argument is that because in the UK this ‘new feminism’ is situated within a particular context of heightened awareness of sexual violence, it has a strangely mundane and universal appeal. As a result we are in danger of diluting or abandoning hard-won approaches that link class inequalities, racism, anti-migrant sentiment and policy, and sex-positive approaches to feminism.

In the UK, the notion of feminism as over, as having achieved its job, or indeed - even if it has not - as being tied to an essentialism better left behind and replaced by more intersectional approaches, has been consistently used to justify the moving of gender and women's studies departments (back) into specific disciplines, or indeed as a rational for closures.

To start, I want to situate some of these questions within the context of recent and current work I have been engaged in on the temporality of feminist theory, the question of feminist politics and subjectivity, and our investment in particular narratives of transformation. In Why Stories Matter (Hemmings 2011), I argued that both claims of progress in which gender equality just needs a final push in order to be achieved, or in which the present of feminist theory is positioned as increasingly sophisticated (and in particular less essentialist), and claims of loss, in which real feminist critique has been all but abandoned, usually because of a myopic younger generation (in or outside the academy), do a similar temporal work. They both position a prior feminism (of complaint, of embodiment, of political integrity or universality) as largely displaced, and reinforce progress narratives in which we build towards an ever more open and sophisticated feminism (even if that requires a return to saner times, a recuperation of what has been lost). Such claims about the temporarily of gender are not particular to feminism; they mirror and inflect broader institutional uses of ‘gender politics’ which similarly tell a particular historical story to validate a particular set of current actions and an imaginary future. If feminism has become increasingly democratic (whether we celebrate or lament this trajectory), it might cause us to pause when we consider that the exporting of democracy also carries this fantasy of inclusivity (often as an alibi for extreme violence). Here too feminism itself is positioned as anachronistic, useful only as a political mobilization no longer needed in democratic modernity, or as the political impetus to others to ‘catch up’ so they won’t need feminism for very long either. It may be faintly embarrassing to have to carry feminist analysis in a forward-looking portfolio, but this too demonstrates the extent of care for the backward other—I’ll look back in time in relation to my own culture so you can move into the present in yours.[1] I tried to reflect that in Why Stories Matter by thinking about feminist methods to challenge linear progression of thinking and action (dystopian or utopian), and to allow us to ‘sit with’ incommensurabilities a while longer.

In my more recent work on Emma Goldman, the early 20th century anarchist activist and theorist, I continue to explore these questions in terms of how we can ‘do history’ while refusing such singularity. Serious consideration of Goldman does open up how we think about the past of feminist thought and action, in my view, and forces a re-framing of where we think we are now. So, for example, I began this work interested in Goldman’s strong gender and sexual politics that never inhered in a feminist identity, thinking that this might offer something important for a contemporary feminist politics that does not rely on nostalgia in order to make its claims, nor on an overstated distinction between feminist and other subjects. Goldman was both consistently irritated with women, damning of femininity and formal redress (franchise), and insistent on women’s real emancipation as key to revolution. And she emphasised the importance of quality over quantity in her attention to sexual politics, which she saw as fundamental to questions of social transformation and labour, as both intimately bound to but also potentially transformative of capitalism. Goldman was always keen to foreground women’s and men’s sexual roles as implicated in nationalism and militarism, and thus she insisted that reproductive politics (birth control, sexual freedom) and an internationalist agenda should always be combined. Goldman was concerned to link prostitution, anti-immigrant feeling, and capitalism in some of her strongest analysis, offering a challenge to single-issue politics that has real resonance today: not simply in affirming the significance of anarchism, but in challenging progress and loss narratives that presume we always know better now than (they did) then.

Yet while in Why Stories Matter I was particularly cautious about a desire to set straight what I saw as problematic stories about feminism, my affair with Goldman is marked instead by caution about the desire to leave certain things behind. While still wanting to ‘release’ Goldman in the present, I have become even more intrigued with what it is that we—myself and other critics who enjoy her work—want to abandon. The aspects we are less keen to claim can be framed as symptomatic of her era, a series of blindnesses that we can consign to the past in order to ensure that the present remains a place within which we can be certain of our position. In my enthusiasm for bringing Goldman forward as a heroine able to resolve current tensions between feminists and other subjects of sexual politics, in my claiming of her as a kind of ‘intersectional’ precursor, or queer interlocutor attentive to sexuality and capital ahead of the game, what do I need to ignore, sideline or repress? In psychoanalytic vein, then, in addition to considering what Goldman might open up in the queer feminist present in direct ways, I also want to tease out what I ‘know but must deny’ (Scott 2012, 67) in my relationship to Goldman as I shuttle back and forth between past and present to make the present mine. What can I say about what I may be trying to forget, but which continues to insist, keeps on interrupting the neat narratives of self, theory and politics I have a vested interest in? In Goldman, what we clean up is her vitriol to women, her focus on sexual nature and the essential goodness of humanity, and her sidelining of race politics in the US context she engaged. Yet we might say that feminism will always involve a judgment of femininity that sticks to women and that faith in human nature remains central to political hope. Most people are ambivalent about their desire, and the relationship between race, class, and gender in the present is less easily articulated than the celebration of intersectionality would perhaps have us believe. We know these things, but we provide narratives, theories and methods that suggest they have indeed been (or can finally be) resolved.[2]

As you can see my concerns remain tethered to questions of temporality, history and community; theory and the subject of feminism; and the mutual imbrication of gender, sexuality and race. In political terms, I am interested in identifying what I perceive to be current political and intellectual difficulties for what Weigman (2014) terms ‘queer feminist theory’, without always assuming we are part of the solution to these difficulties rather than participants in their instantiation and perpetuation. In particular, I have been (and continue to be) interested in the amenability rather than co-optation of feminist narratives of past, present and future for other agendas, because a discourse of co-optation reserves the initial feminist space of articulation as politically pure, an assumption I find unpersuasive. Yet how can we assume non-innocence and still act, make community, and imagine the world as other than it is now?

2. (Still) Telling Feminist Stories

Until 4 or 5 years ago in the UK, and in line with my arguments in Why Stories Matter, feminism was positioned as largely anachronistic: surpassed, stereotyped as angry, ugly, anti-male (or too masculine), out of step with the interests and needs of contemporary politics and culture. Where ‘gender equality’ was made visible it was emphatically not tethered to feminism (except temporarily or by association, as indicated above), but taken up as part of new democratic freedoms, for example in Iraq or Afghanistan, or within mainstreaming agendas that would have made Goldman’s hair curl. Alternatively, a spectre of that same equality was sutured to a ‘postfeminism’ characterized as embracing sexual and gendered emancipation as if it had already been achieved.[3] In the latter context, ‘postfeminist’ agency has been primarily represented through the take-up of femininity over feminism, in depressingly predictable ways. Such debates have been framed as generational to a large extent, with the young being on the side of (feminine) sexual freedom, and the old on the side of (feminist) sexual sanction, with affective characterisations of generosity and curiosity on one hand, and bitterness and misplaced certainty on the other. Feminism has thus been positioned as anachronistic in two senses – part of a prior era, and belonging to the old themselves (McRobbie 2009). The explicitly feminist critique of such vicious misrepresentations of a displaced feminism (though not of the young women positioned primarily as political dupes) has frequently reproduced a similar generational logic: positioning young women as departing from feminism but continuing to enjoy its (limited) privileges. Thus young women are consistently characterized either as uniquely subsumed under a new sexualisation of culture, one that exploits precisely this fantasy of sexual agency as part of continued objectification,[4] or, as Zora Zimic (2010) has pertinently noted, they are positioned as duplicitous, regulated in gendered terms by the prejorative grammar of ‘I’m not a feminist, but…’[5]

Within European academia, we have also witnessed the institutionalisation of various modes of ‘feminism as anachronism’. Within Southern Europe, where feminist work was never fully institutionalised (for various complicated reasons, not least the requirement of ministry recognition for disciplines in most countries North and South), Gender Studies has been taken up as a means to showcase ‘modernity’ within a European context (Pereira 2014). But this of course has implications both for the kinds of work taught (policy- and equality-oriented, over and above the struggling humanities which has long been its covert home), and for the precarity of the field (since EU funding is temporary, and its political character unstable). In the UK, the notion of feminism as over, as having achieved its job, or indeed—even if it has not—as being tied to an essentialism better left behind and replaced by more intersectional approaches, has been consistently used to justify the moving of gender and women’s studies departments (back) into specific disciplines, or indeed as a rational for closures. The UK now has no undergraduate degree provision in gender and women’s studies, although courses and ‘concentrations’ remain at the better-funded sites. Interestingly, this discursive rendering of feminism as no longer necessary can be evidenced by high or low numbers of students and interest, providing an encompassing conservative rationale that masks the ideological basis for such institutional aggression. The fundamental irony of being accused of being too simplistic in our political views, too identity-based, too concerned with and attached to fictional inequalities, by colleagues with no history of interest in social justice has not been lost on feminists struggling to have any version of feminist analysis accepted as legitimate. But so too, I think, those who call this complex field home have also participated in progress and loss narratives whereby feminism’s ‘proper object’, gender, first displaces ‘women’s studies’, then is itself displaced (or qualified) by ‘sexuality’ in a succession contest of our own. The inhabiting of ‘queer’ as more plural than poor old rusty feminism with (her) cis-identifications of women’s essential bodily truth and tired attachments to identity can be a rehearsal of the same story (Hemmings 2014). Such attempts to find the right ‘object’ that will finally do the multiple work we crave, as Robyn Wiegman has pertinently noted in Object Lessons (2012), marks some objects as more amenable to pluralisation than others, of course: feminism appears to be brittle and caught in her bad past; queer theory seems ever associated with the most transgressive possible interpretations. It is curious how much power feminism has in such narratives, even in the moment of its displacement.

-

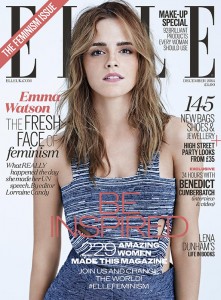

In 2015, while many of the above dynamics endure, we are also in the midst of some important shifts. In the UK, feminism appears no longer to be a dirty word; in fact, if anything, across media, cultural and social movements it constitutes a new political force that has a broader, almost universal appeal. In celebrity culture, in ways that it no one would have anticipated, feminism is now consistently referenced not as an unshaven relic from the past, nor as something to be thankful for (but also thankfully over); instead it is as the new, caring position to take up if one is to be properly ethical and political. In February 2014, Marie Claire had a special section headed ’10 Signs That You’re a Feminist’, and in November Elle UK launched its ‘Inaugural Feminist Issue’, with the actor Emma Watson as the ‘cover girl’ following her speech at the UN on gender equality. Both fashion magazines sought to give feminism the makeover she deserved, emphasizing the contemporary empowered woman’s embrace of femininity and romance in familiar vein. But there was also an important difference too, namely a new attempt to suture femininity and feminism rather than keeping them apart. Marie Claire‘s title was followed with the subtitle ‘Hate to break it to you, F-word haters, but you’re probably more of a feminist than you think’, which retains the original grammar of distance, but now seeks a rapprochement after the pause. Elle‘s special issue was launched after Karl Lagerfeld’s catwalk event ‘Stylish Suffragettes’ in September 2014, with models carrying placards saying ‘FEMINISTE MAIS FEMININE’, emphasizing the linking of culturally hitherto opposed forces (though the ‘mais’ rather than ‘et’ begs the question of course). And Elle‘s own special issue claimed Emma Watson as the ‘fresh face’ of feminism, referencing once more the assumption that feminism will not have that kind of a face, but claiming feminism otherwise. Elle combined their feminism issue with a line of ‘This is What a Feminist Looks Like’ t-shirts, donating the proceeds to The Fawcett Society feminist campaigning group who coined the wearable phrase in the UK. What was so extraordinary about this campaign was the number of women and men in the public eye that they managed to persuade to wear and be photographed wearing one: from Harriet Harman and Emma Watson, to Benjamin Cumberbatch, to Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg. If we note that they do all look faintly embarrassed—a million miles away from your own president’s feminist superhero determination for Ms. Magazine in 2009—perhaps that is because of an uncanny anticipation of the subsequent scandal about the context of the Whistles’ t-shirt production in Mauritius under exploitative labour conditions.[6] The campaign was also marked by general concern about our Prime Minister David Cameron’s refusal to wear one, prompting a somewhat surreal set of broadsheet and tabloid interrogations as to why he should be squeamish about embracing this affirmative identity.[7]

It is easy enough to be straightforwardly cynical of such cultural voracity as just the next marketing ploy to sell magazines (like everything else, it turns out that anti-feminism has a shelf life), but this fashionable feminist visibility is shared by the broadsheets, and by the resurgence of feminism as a social movement. Most prominent among these is UK Feminista, which emphasises women’s sexual inequality as the primary site of their oppression, and takes up the anti-porn, anti-sex work banners many of us thought might be a thing of the past. At LSE we began the new academic year with a public lecture on ‘Gender, Inequality and Power’ that created a new media storm resulting in 600 people trying to attend and a spill over room for people who could not get in.[8] At a political level within the institution, the circulation of misogynist, homophobic and racist leaflets by the rugby team at the start of the academic year was nothing new, but the community response was unprecedented. Not only was LSE’s senior management forced into making public statements condemning the sentiments, in addition to the investigation into the incident itself there was also a sustained focus on the broader political culture at LSE as condoning rather than challenging such inequality.[9] Perhaps we are indeed seeing the emergence of a new era of popular feminism and gender equality, a rethinking of the grammar of generational alienation.

3. Contextual Feminist Stories

I want to pause a little to look at my own representation of these shifts and emergences with respect to feminism here. I have framed the story as one of prior marginalisation of feminist issues into one of their centrality, and there is a tacit tone of ‘surprise’ in my brief story that frames these events as a potential repoliticisation, whatever my critique of this kind of progress narrative might otherwise be. In this respect, my own storytelling suggests an investment in the grammar of ‘I’m not a feminist, but…’ as having been thoroughly apolitical too, though I would have distanced myself from that position if directly asked. And yet—as many critics and activists said from the heartland of a post-feminist era I laid out above—the populist pull of ‘anti-feminism’ was not the only thing embedded in that grammar, particularly among the third-wavers unfairly over-associated with these cultural dis-identifications from the demon mother (Gillis, Howie and Munford 2007). As theorists such as Christina Scharff (2012) and Jonathan Dean (2012) have insisted, that ‘but’ may also and consistently does indicate an intersectional, politicised critique of feminism, even while it can also slip into vilification. Thus ‘I’m not a feminist, but…’ has also been thought through as a way of expressing dissatisfaction with single-issue politics, or articulated as part of a black feminist critique of the limits of feminist inclusion. An active, deliberate critique not just of gender politics ‘out there’, but also of feminist norms and exclusions, part of a refusal rather than acceptance of sexualised culture and neoliberal values (see also Lumby 2011). In relation to what Dean (2010) and Bice Maiguashca (2014) insist is an unprecedented growth in feminist activism globally (as part of other movements or independently), a loss narrative seeks to make exceptional what might better be thought of as inevitable.[10] Might my own surprise at a feminist resurgence reference a preference for the lament over a shift in perspective about who the author of feminism is and what feminism should include?

Seeing these emergent feminisms as signs of progress, loss or even stasis is perhaps to miss the broader social and material conditions that are reshaping a complex Europe-wide terrain of gender inequality. First we might point to the gendered consequences of austerity: across Europe, the cuts in public funding are felt more keenly by women, who are both poorer earners in public sector work and already subject to the pay gap.[11] So too women are the ones called on to pick up the slack when social resources are withdrawn. Understanding what is happening here in terms of ‘re-traditionalisation’ of gender roles is only of limited help for making sense of women’s role as the ‘reserve army’ of labour. The repeated—not so much precarious, but fundamentally temporary—nature of women’s access to the labour market has always required naturalisation in order not to appear as it is: a privileging of a male breadwinner model that represents both patriarchal and state interests. Progress and loss narratives within feminism have, I think, prevented us realizing that the limited gains that we have seen – in employment, health, education, law and visibility – are always (as Goldman would have insisted) subject to the capricious power of authority. A discourse of ‘re-traditionalisation’, then, participates in the same game, reading current manipulation of gender norms as a ‘return’, a failure of the present to move beyond its past, rather than as an enduring condition of gendered discourse. The apparent desire to include women as full and equal participants in the public sphere (or to present them as already such participants) is necessarily contradicted by the creation of conditions that prevent them from being able to participate: this is, to my mind then, less a paradox or temporal lag, than the precise mode through which enduring inequality is naturalised and displaced.[12]

From the perspective of my current project, though, even a less linear – but still quantifying – approach misses the mark. An increase in women’s employment or participation has never in fact meant a concomitant decrease in their unpaid and caring labour but is likely to mean an increase in overall working hours (Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2010, 98-103), precisely because women as well as men are as likely to defend men’s heterosexual and gendered privilege in the private sphere as they are to challenge it. The often-overlooked point here is that women as an invisible reserve army works to the extent that gender roles remain woefully unchallenged within a heteronormative domestic frame; the idea of ‘re-traditionalisation’ resonates insofar as it obscures the fact that the conditions are already there (Berlant 2011).[13] For all the work on formal equality, the question of how to become subjects able and willing to transform our lives relationally in order to generate sustainable equality remains opaque.

Lastly, we might suggest that the newly vibrant feminist movements that focus their attention on sexual violence are extraordinarily successful at least in part because of the ‘sexual abuse scandals’ that have burst through from the past into the present in the last several years in the UK. A whole slate of ageing celebrities have been accused, tried and found guilty of sexual abuse in the 1970s (and beyond), a set of revelations that has implicated national institutions such as the BBC, the NHS (particularly mental health services), social services (particularly child protection), the civil service and government. The picture is one of rampant violence and misogyny that was overlooked and minimised, taking decades to emerge as those abused found the courage to speak out (again). The misogyny and violence are often presented as uniquely horrific, and thus simultaneously minimised, as though we could not expect anything else of the 1970s. To do so the 1970s itself has become represented as singularly accepting of sexual violence, curiously free of feminist or left detractors, chock-full of passive young people and women, and predatory men (a time indeed when feminism was necessary, but importantly not present in this cultural account). What we are left with instead is a sanitised progress narrative in which it is supposed that such abuses would not and could not happen today, despite rape and sexual violence remaining under-reported and prosecuted, with recent reports indicating this is getting worse rather than better.[14] Depressingly, one might says that feminist groups such as UK Feminista are thus in a strong position to appeal to the one kind of feminism that everyone can agree on: one that identifies sexual and gender-based violence as the basis of gender oppression, while simultaneously positioning sexual violence as part of the actual or (soon to be, as it is already) psychic past. Feminism is already culturally and imaginatively associated with a clear division of the world into men and women, into violent actors and victims, and since no one is likely to come out as ‘in favour’ of sexual violence, there can be a rather uneasy alliance between sexual violence feminism, media feminism and the law that all but closes the circle.

To return to the popularity of ‘looking like a feminist’, then, to don the t-shirt might thus be said to be a way of marking oneself out as ‘not one of those old misogynists’, and to signal a break with anti-feminism (which would now be cast as both old-fashioned and pro-sexual violence). But to take up this position is also to take up a pro-censorship and anti-prostitution position that has long characterised such forms of feminism. Again, this is uncontroversial for celebrities and politicians whose careers can be decimated by the smallest whiff of the sexual scandal that porn and prostitution suggest. But in the process, both sexual violence feminism itself and those who celebrate it write out the complex debates over the nature of sexual violence, the significance of porn, or the character of sex work, that have been central to feminism since its inception.[15] So too the intersectional critiques of this strand of feminism – as perpetuating racial and classed stereotypes in their preference for marches in poor neighborhoods, or as ignoring the complex modes of oppression and freedom that different women and men face—are positioned as ‘diluting’ a clear agenda in ways that are extremely familiar. Sexual violence feminism fits—as it has done for over 150 years—with the progress narratives of modernity and democracy that mark other contexts and cultures as uniquely patriarchal through their failures to place sexual violence in their own pasts (even when—or most especially when—this failure might be said to mark all states and cultures).

At an institutional level, and at the media and cultural levels, the new popular resurgence of feminism reveals some interesting contemporary features of feminist politics and temporality. Moves toward equality and diversity in my own institution are framed as universally desired and desirable, just as they are in bourgeois fashion magazines such as Marie Claire or Elle. Everyone is in favour of equality now, and no one is responsible for inhabiting the privileges of inequality, let alone for being a misogynist (since this is a spectre burst through from the past). If the choice is about being a subject of equality or its violent obstacle, this is really no choice at all. But in the widespread and necessary take-up of a pro-feminist position, the historical and contemporary erasures are chilling. Anyone can be a feminist, not matter what they do, how they behave, or who they cast out or even kill, as long as the violence is not sexual. As I have begun to argue here, the claim that anyone can be a feminist, and that equality is in everyone’s interests and on everyone’s mind, functions to deflect attention from the profoundly material ways in which this is so evidently not the case. Worse, that insistence on full recognition as either already having happened or about to happen is a central means of ensuring that any real intersubjective or cultural change does not happen (since there is no need for it).

Concluding Dilemmas

If feminism is in part discursively and culturally vibrant because of its capacity to deflect political complexity through the assertion of self-evident truths—feminism is universal; everyone wants equality; no one is in favour of sexual violence—then we should not be surprised that the shame of wearing the t-shirt did not attach to the singular lack of evidence of interest in gender equality or sexual politics failure by those celebrities and politicians wearing it, but rather to the possibility of being implicated in global economic and racial inequality. Being a feminist should provide the ‘way out of’ not the ‘way into’ such intractable horrors so affectively mismatched with the pleasures of t-shirt politics. If I am (even partly) right in my reading of feminism’s current modes of articulation, feminist theorists face a peculiar dilemma. On the one hand, we would want to encourage the broader take-up of feminism in the world, expecting surely that it will not necessarily mirror one’s own concerns. But on the other hand, if ‘feminism’ or ‘gender equality’ function specifically as tropes through which ongoing inequality is managed or even ensured rather than alleviated then this may require taking a break from ‘representations of feminism’ if not from feminism itself (to paraphrase Janet Halley), precisely in order to reinvigorate its politics and practice in relation to its current mobilisations.

For the moment, I want to suggest two ways of taking this break that draw on Goldman’s insights as I have outlined them in this paper. The first is to disarticulate feminism from her presumed feminist subject as a way of politically animating that ambivalent ‘but’. Importantly, while Goldman dis-identified from feminism, she did not exit the scene of gender and sexual politics: quite the opposite, she fought tooth and nail throughout her life to improve conditions for women. For Goldman, though, women and men needed first to focus on their internal demons in order to effect real and lasting change, taking responsibility for (and struggling with) their own conservative as well as radical desires in relation to others. Where Goldman would depart from this contemporary grammar is where it expresses an unqualified desire to retain femininity as part of class mobility or raced respectability, since she framed that dis-identification as a mechanism for increased not decreased solidarity. We also need to insist on this grammar of dis-identification as widespread rather than generational. One might say, indeed, that one thing that could be said to unite women across generations is their consistent rejection of and dis-identification from feminism. As a political movement that (ambivalently and imperfectly) challenges the roots of femininity as heterosexist, classist and racist, a second tactic might be to reclaim feminism as the very definition of a minority pursuit, one involving judgments of and struggles over the terms femininity and feminism, as well as their relationship to one another.

Notes

- We might well take a warning from Sara Ahmed here (2004), who points to the ways in which fantasies of transcending histories of violent difference are a central mechanism to ensure reduced accountability for the messy business of historical and contemporary implication in, rather than freedom from, power relations.

- I raise some of these issues—as well as the question of affect in imagining feminist history—in “Considering Emma” (Hemmings 2013).

- See Interrogating Post-feminism (Tasker and Negra 2007) for a comprehensive collection of interventions into ‘post-feminism’ and popular culture in Anglophone contexts.

- Ros Gill’s work on sexual subjectification as the new mode of oppression has been particularly important in this regard (2003). While not an intent of the work itself, in the context of progress and loss narratives, ‘sexual subjectification’ as the new objectification reinforces the assumption that duped action is particular to young women.

- Zimic is one of the few commentators on this grammar who considered competing reasons why young women might want to mark their distance from feminism, but still want equal treatment. She argues that the ‘I’m not…’ could as easily be read as an unease about whether they possess feminist ‘competence’, and that the ‘but…’ might serve as rapprochement.

- Rosie Boycott broke the story for the Mail on Sunday in her piece “Scandal of the 62p-an-hour T-shirts: Shame on the Feminists Who Betrayed the Cause,” in November 2014, which was then refuted by Chris Johnston in his article for The Guardian, “Feminist T-shirts Made in Ethical Conditions, Says Fawcett Society,” also in November.

- My own allegiances lie with Homa Khaleeli, who points out in her article for The Guardian, “David Cameron: This is Not What a Feminist Looks Like” on 27 October 2014, that “feminism is not just about wishing for women and girls to have the same rights and opportunities as men: it is a movement created to ensure that it happens. It is about actively working with women to change the status quo. And given Cameron’s record so far, one thing is clear: this is not what a feminist looks like.”

- Diane Perrons “Gender Inequality and Power: The Gender Institute Orientation Public Lecture,” 1 October 2014.

- A 17-page report on sexism and LSE culture was recently published recommending (among other things) the establishment of a funded ‘Task Force’ for equality and diversity LSE Publishes Final Report on Incidents of Sexism and Homophobia on Campus: http://www.lse.ac.uk/intranet/staff/equalityAndDiversity/home.aspx.

- As Dean helpfully points out, even with repeated examples of ongoing attachments to feminism among young people contemporarily and the growth rather than demise of feminist social movements globally in the last ten or so years, “claims that young women are not feminist… are so entrenched in the feminist imagination that they remain largely untroubled even by empirical counter-examples” (2012, 316).

- See the recent issue of Feminist Review, “The Politics of Austerity” (Brah, Szeman and Gedalof 2015) both for a feminist analysis of various aspects of austerity, and for approaches within feminist economics that propose alternatives.

- We might do better, perhaps, to focus on the cyclical nature of gains and losses that dog all political movements, where the gains can be got rid of overnight it seems, while the losses take decades or even generations to recover from. I have been thinking here of Wendy Brown’s brilliant work on States of Injury (1995) in which she identifies the problematic (political and affective) attachments to injured identities as central to Left movements. In the present we are dealing perhaps with both injured states and subjects and with fantasies of those injuries having been overcome, at least in feminist terms, as one mode through which continued authority exerts its force.

- For Berlant, such fantasies of attachment provide value and depth to our lives where the broken social contract (for men) cannot.

- See http://www.cps.gov.uk/publications/docs/cps_vawg_report_2014.pdf for Crown Prosecution Service statistics relating to increased reporting but decreased convictions for rape of women and girls in the UK.

- Having attended several open events run by UK Feminista or other similar organisations the lack of interest in taking on these debates is striking. This is perhaps another salient lesson—that it is easy to think that political debates have been won in a particular direction, only to find yourself having the same conversation in a different context decades later as if that debate had never happened.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2004. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 79 2 (2): 117-139.

Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Brah, Avtar, Ioana Szeman and Irene Gedalof, eds. 2015. “The Politics of Austerity.” Feminist Review 106.

Brown, Wendy. 1995. States of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late Modernity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Dean, Jonathan. 2010. Rethinking Contemporary Feminist Politics. London: Palgrave McMillan.

———. 2012. “On the March or on the Margins? Affirmations and Erasures of Feminist Activism in the UK.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 19 (3): 315-329.

Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2010. The World’s Women 2010: Trends and Statistics. New York: United Nations.

Gill, Rosalind. 2003. “From Sexual Objectification to Sexual Subjectification: The Resexualisation of Women’s Bodies in the Media.” Feminist Media Studies 3 (1): 100-106.

Gillis, Stacy, Gill Howie and Rebecca Munford, eds. 2007. Third Wave Feminism: A Critical Exploration. 2nd ed. London: Palgrave.

Halley, Janet. 2006. Split Decisions: How and Why to Take a Break from Feminism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hemmings, Clare. 2011. Why Stories Matter: The Political Grammar of Feminist Theory. Durham NC: Duke University Press.

———. 2013. “Considering Emma.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 20 (4): 334-346.

———. 2014. “The Materials of Reparation.” Feminist Theory 15 (1): 27-30.

Lumby, Catharine. 2011. “Past the Post in Feminist Media Studies.” Feminist Media Studies 11 (1): 95-100.

Maiguashca, Bice. 2014. “‘They’re Talkin’ Bout a Revolution’: Feminism, Anarchism and the Politics of Social Change in the Global Justice Movement.” Feminist Review 106: 78-94.

McRobbie, Angela. 2009. The Aftermath of Feminism: Gender, Culture and Social Change. London: Sage.

Pereira, Maria do Mar. 2014. “The Importance of Being ‘Modern’ and Foreign: Feminist Scholarship and the Epistemic Status of Nations.” Signs 39 (3): 627-657.

Scharff, Christina. 2012. Repudiating Feminism: Young Women in a Neoliberal World. London: Ashgate.

Scott, Joan. 2012. “The Incommensurability of Psychoanalysis and History.” History and Theory 51 (February): 63-83.

Simic, Zora. 2010. “‘Door Bitches of Club Feminism’? Academia and Feminist Competency.” Feminist Review 95: 75-91.

Tasker, Yvonne and Diane Negra, eds. 2007. Interrogating Post-feminism: Gender and the Politics of Popular Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Wiegman, Robyn. 2012. Object Lessons. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

———. 2014. “The Times We’re In: Queer Feminist Criticism and the Reparative ‘Turn’.” Feminist Theory 15 (1): 4-25.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License