Trash is an essential component of our daily lives. We produce trash by discarding the leftovers of what we consume as well as what we no longer use. We find trash everywhere: at home, in our office, in rubbish bins, in the street, on the grass, on the sidewalks. Everyday waste is rather ubiquitous even though we may not notice it. Its pervasive nature stems from our lifestyle that is shaped by a mechanism of use and disposal that increasingly produces more waste. Martin Melosi, in his seminal work, Garbage in the Cities ([1981] 2004), demonstrated that refuse and waste are urban problems that usually have been solved by removing them to a space "out of sight." The displacement of garbage comes to represent in the social imaginary the "ominous" and "contagious" elements that need to be eradicated. Yet, British anthropologist Mary Douglas, in Purity and Danger ([1966] 2002), examined the role of the impure and residual as a social category emphasizing the cultural associations we have with each of them. Our rejection, she claims, is only part of a pre-established system where "dirt" is matter in the wrong place.

Trash is so abundant that we are unintentionally creating multiple archeological sites. Besides producing landfills, which are usually placed away from urban centers, we are erecting these enormous monuments to modern technology in Africa, Asia, and Latin America by disposing nuclear waste, technological leftovers such as old computers and printers, medical equipment, or home appliances.

Trash is so abundant that we are unintentionally creating multiple archeological sites. Besides producing landfills, which are usually placed away from urban centers, we are erecting these enormous monuments to modern technology in Africa, Asia, and Latin America by disposing nuclear waste, technological leftovers such as old computers and printers, medical equipment, or home appliances: microwaves, fridges, AC units, vacuum cleaners, and ovens, among many more. But these objects are also making their way into the oceans, rivers, and atmosphere. We fabricate residues through the pipes of large factories, power plants, and oil refineries. We could well understand the history of modern technology by examining what we throw away, as archeologist William Rathje has demonstrated in his "Garbage Project" of 1971. Guided by the question of whether it is possible to analyze and research human behavior by examining trash, Rathje and his team embarked on a research project that aimed to study the use of economic and nutritious resources in the American home. For this purpose, he scrutinized contemporary solid waste. Modern garbage dumps represent an indisputable legacy of current industrial urban society, and still trash has not been addressed nor considered an object worthy of scholarly attention. A broader definition of trash study—or garbology—should incorporate, according to Michael Shanks, David Platt, and William Rathje (2004), not only waste, remnants, leftovers, and scraps, but also ruins, decaying matter, hygiene, and dirt, as well as diseases. Therefore, and given the significant connection between waste generation and urban environments, trash matters because it is at the core of both the constitution and decomposition of modernity.

Over the past several years, my research agenda has focused on trash in Latin America, paying particular attention to how recent Latin American representations are infused with a narrative of waste and disposal in relationship to both the conservation and destruction of nature (Heffes 2013). To give an example, I have been working on the trope of environmental destruction. This trope is related to a corpus of aesthetic material from Latin America where the image of the landfill is predominant, and where discarded waste in these sites constitutes the daily food and provisions for thousands of people living in marginality and poverty.

My research agenda has focused on trash in Latin America, paying particular attention to how recent Latin American representations are infused with a narrative of waste and disposal in relationship to both the conservation and destruction of nature.

Some examples are films and documentaries like the 1989 Brazilian Ilha das Flores (Flowers island) by Jorge Furtado and the 1993 Boca de lixo (Mouth of garbage) by the recently deceased Eduardo Coutinho. In narrative, the novels Única mirando al mar (Única gazing at the sea, 1994), by Costa Rican Fernando Contreras Castro, and Waslala, by Nicaraguan Gioconda Belli (1996), are paradigmatic. And in the visual arts, the work of Argentine painter Antonio Berni (1905–1981), especially his series on Juanita Laguna and Ramona Montiel, is remarkably illuminating. From both a poetic and critical perspective, the images articulated in these representations bring to light the unsettling effects of globalization where modern economic forces have marginalized people, leading them to live in non-human conditions (such as living in the landfills) and to become what Zygmunt Bauman (2004) has called "wasted lives."

In the same vein, I also have been examining a second trope of environmental sustainability by looking at literary and visual narratives of the junkyard, addressing specifically the practice of recycling and reusing. What is revealing from these materials is that, unlike in the United States or Europe where this activity is informed mainly by an ideological initiative, in Latin America recycling represents the only income-generating opportunity for many people who have lost their jobs and cannot reinsert themselves in the labor force due to dire economic conditions. They are called catadores in Brazil, cartoneros or cirujas in Argentina, buzos in Costa Rica, gallinazos in Colombia and Peru, and pepenadores in Mexico. Of course, this phenomenon is not limited to Latin America: in Dakar they are called facks and teugs, wahis and zabbaleen in Cairo, and scavengers or garbage pickers in English-speaking countries (Castillo Berthier 2010, 137). What all these names reveal is a common activity: to make a living out of trash. With the "globalization of poverty," as Mike Davis accurately defined it in "Planet of Slums" (2004), marginality has also become global.

With regard to recycling in Latin America, some examples are the novels Mis amigos los pepenadores (My friends the garbage pickers, 1958), by Mexican author José Luis Parra, La villa (The Slum, 2001), by Argentine César Aira, the short story "Greenpeace" (2000), by Cuban Eduardo del Llano, and the play Homens de papel (Men of paper, 1978), by Brazilian Plínio Marcos. As for the visual narratives, the documentary Cartoneros (The Scavengers), by Ernesto Livón Grosman (2006), conveys the abrupt social changes that have been disrupting the lives of ordinary Argentines after the economic crisis in 2001, emphasizing the transformations within the middle classes who have been reduced to rummaging through garbage in order to survive.

I would like to emphasize that residual culture in Latin America is located at the intersections of trash production, modernity, and urban environments. If Latin American cities are the privileged spaces of modernity, they have also become sites of large-scale waste generation.

Before we look in greater detail at some examples of the work enumerated above, I would like to emphasize that residual culture in Latin America is located at the intersections of trash production, modernity, and urban environments. If Latin American cities are the privileged spaces of modernity, they have also become sites of large-scale waste generation. Because of this, they represent critical spaces of environmental degradation, with large residual concentrations that pose a real health threat for the surrounding populations who are often among the underrepresented.

My first case study is the documentary Boca de lixo (Mouth of garbage, 1993) by Eduardo Coutinho, which was shot in the garbage dump of Itaica, on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro (40 kilometers away), in the municipality of São Gonçalo. This is one of hundreds of sites where men, women, and children, or catadores, retrieve aluminum cans, glass bottles, cardboard, and plastic, as well as food, clothes, and other artifacts that they may reuse. Unlike other scavengers and rag pickers, these families live in the landfill. Through the camera’s framing of the space with a long shot that renders both people and their makeshift homes—a euphemism to refer to the tents composed of plastic bags that serve as shelter—frail, ephemeral, and unsafe, Coutinho’s perspective emphasizes that the catadores straddle the border between the existent and non-existent, amid permanency and evanescence.

Adopting the format of a series of interviews, the documentary consists of a set of one-on-one conversations with different people who live in the landfill and who narrate their experience of inhabiting this space. A pioneer, Coutinho makes a visible effort to avoid both presenting these interviews as coercive interrogations and cataloging individuals in well-worn stereotypes. Instead, the documentary displays an informal conversation with multiple narratives. Far from creating a unique account, these open-ended narratives point in different directions. His position as a documentary maker was precisely to inquire into how interviewees established and interpreted the relationship between themselves and the space of the garbage dump (Coutinho 1997, 169). Coutinho explained this effort as one that avoided the middle-class intellectual consciousness that abhors these families’ activities. A striking example is when he chats with a woman who lives in the landfill with her children.

- Stills from Boca de Lixo (Mouth of Garbage), 1993. Source: YouTube.

This scene shows two different narratives: first, the oral account of the woman who states that she has a good life, and that her children, who were raised there, "are all healthy"; on the other hand, the visual account through the angle of the camera—simultaneous to the woman’s oral account—focuses on a pile of disposed syringes along with other hazardous material most likely from a hospital. The camera then travels to her feet, stopping at an open wound the woman claimed to have obtained from one of the needles. The following framing of the woman and her children walking barefoot in the landfill not only juxtaposes several registers (an oral and a visual in this case) but also displays the sharp contrast between an illusionary perception of a healthy environment and a reality that is both contaminating and toxic. This is what Argentine sociologists Javier Auyero and Débora Swistun (2009) have defined as "environmental suffering." Boca de lixo therefore displays numerous accounts without guiding the gaze of the spectator in one direction or the other. It thus will be up to the spectator to decide and prioritize either the oral or visual narrative, or both.

My second case study is Única mirando al mar (Única gazing at the sea) by Costa Rican Fernando Contreras Castro ([1993] 1994), which narrates the story of an unnamed man who is fired from work and, in an attempt to commit suicide, throws himself into a trash bin. To his surprise, however, he does not die but instead ends up in the largest landfill of San José de Costa Rica, where Única, one of the female buzos (Spanish word for "divers"), finds him. After the encounter, she then decides to recycle his existence by giving him a new name. Like the man, Única was a teacher and was then laid off when she turned 40 years old. The novel takes place for the most part in this landfill—which is referred to ironically as the "dead sea"—where the buzos work every day retrieving the "re-usable" garbage that is dumped from the garbage trucks, competing with ravens, rodents, or among themselves, like in another memorable short story, "Los gallinazos sin plumas" ("Featherless Vultures," 1954), by Peruvian author Julio Ramón Ribeyro. The material found is then used for personal consumption, for bartering, or for sale. Aluminum cans, glass bottles, paper, and plastic are considered most valuable because they can be collected and then sold to middlemen. Just as she discovered the main character among trash, so too did Única find her own son in the landfill. She once saw a child that was abandoned in the garbage dump wandering among the scraps, so she retrieved him and gave him a home, a mother, as well as a new name. The novel, which ends with the closure of the landfill, which leaves all the buzos homeless, establishes a parallel between the "useful life" of the human and non-human. What it demonstrates is that disposal occurs even though there is still life within subjects and objects. This critique of the massive machinery of consumption, where not only objects but also subjects are continuously replaced, blurs the borders between them, posing a fundamental problem: in the age of mechanical reproduction subjects have become reified, losing their inherently human condition. That is, the mechanism of perpetual reproduction produces at the same time a disposable humanity. Human residue, then, becomes a key component of this society of excess, a society that depletes its resources while at the same time offers no place for those discarded.

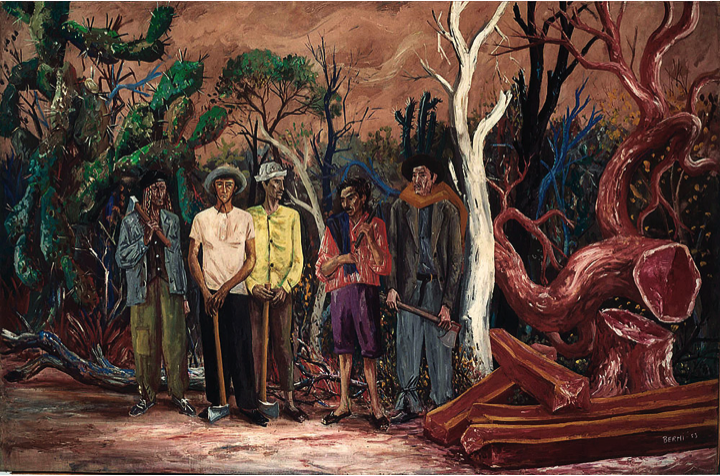

My third case study is renowned Argentine painter Antonio Berni’s series on Juanito Laguna and Ramona Montiel, as well as his earlier paintings on the environmental tragedy that took place in the province of Santiago del Estero, in the northwestern part of Argentina, during the 1950s. Berni completed the series, Motivos santiagueños (Santiagueños’ motives), from 1951 to 1953 as a result of the indiscriminate tree felling of the province’s forest. It is estimated that at least twenty timber merchant companies owned at the time 1,500,000 hectares, and the wood was used for railway tracks as well as fuel for the trains. The ecological predation coexisted with a social one. Most of the profit remained with the owners of the companies, and neither the workers nor the forests received any benefit. Berni, who was affected by the devastation, painted Los hacheros (The Lumberjacks, 1953) and Migración (Migration, 1954), among others in the same series.

Antonio Berni, Los hacheros (The Lumberjacks), 1953. 200 x 300 cm., watercolor on canvas, private collection. Source. Accessed on 7 July 2017.

Around this time period, in Buenos Aires and its outskirts, men, women, and children collected paper, used rags, cans, glass, and even bones for use as a source of heat. Transferring his attention to this urban landscape, Berni portrayed the misery of these garbage collectors in lower Flores’ neighborhood by inventing a character, Juanito Laguna, a young man whose daily survival depends on scraping together all sorts of remnants from the city.

Antonio Berni, Juanito Laguna va a la fábrica (Juanito Laguna going to the factory), 1977. Mixed media, 180 x 120 cm., collection of Anibal Yazbeck Jozami. Source. Accessed on 7 July 2017.

With the creation of Ramona Montiel, another of Berni’s famous characters, the Argentine painter refined his innovative printing technique, called "xilo-collage-relief," a process that involves the recycling of materials from Ramona´s daily life—fabrics, wigs, artificial flowers, brooms, clothes, tinsel, coins, and buttons—and creating molds of them that are then printed in a technique similar to a woodcut. The result yields an impression with elements in very high relief on handmade paper, creating a thick and richly textured printed surface.

Antonio Berni, Ramona costurera (Ramona the seamstress), 1963. Woodcuts and collage, 142 x 55 cm., private collection. Source. Accessed 7 July 2017.

Through his unique combinations of commonplace materials with brutal realism, Berni sought to express the harsh realities of unbridled urban growth in Argentine society at the beginning of the 1960s. The use of waste and obsolete objects to produce aesthetic artifacts that combine recycling activities with social condemnation places Berni at the forefront of environmental art. Although usually not associated with an ecological agenda, Berni’s work established a dialogue between two contemporaneous concerns by raising awareness about the continuous changes in consumption as well as the constantly increasing environmental damage.

These case studies show how trash plays a vital role both at a literal and symbolic level. In very different ways and through distinctive methods, Contreras Castro’s novel, Coutinho’s documentary, and Berni’s paintings inquire into the place of residual culture and how its value is shaped and formative of political, social, and economic environments. Representations of landfills, garbage disposal, or toxic waste vary enormously from case to case, as well as from setting to setting. In Latin American cultural production, garbage works as a category to define what is human and what is not. Trash matters because in our contemporary world, ruled by the laws of the market and consumption habits, trash has become a category that can either separate or unite. Trash defines what is of value and what is not. Through trash we assign a permanent or ephemeral value to things and people. By defining and differentiating between one and another, trash displaces the notion of human and non-human and replaces them with the value of commodities and effectiveness. It can transform human into non-human and imbue the non-human with a sacred dimension. Arjun Appadurai (1988) has already pointed out that commodities, "like persons, have social lives" and thus, "commodities can provisionally be defined as objects of economic value" (Appadurai 1988, 3).

These case studies show how trash plays a vital role both at a literal and symbolic level…These case studies also demonstrate that Latin American representations of environmental issues offer novel contributions to the global field of ecocriticism.

These case studies also demonstrate that Latin American representations of environmental issues offer novel contributions to the global field of ecocriticism. Ecocriticism, as it has taken root in the United States and the United Kingdom, has tended to place emphasis on the humanization of the non-human. Although this theme is by no means absent in the Latin American environmental critique, another concern emerges prominently: the dehumanization of the human by means of daily exploitation, consumption, and disposal.

The three paradigmatic cases I have discussed all intersect with what I call "a rhetoric of waste" because they explore what is discarded and disposed of, what is recycled, and what is preserved. Therefore, all these examples relate to the wider problem of environmental destruction and preservation. In a broader sense, these features allow me to engage with a number of concepts, notably globalization as well as environmental justice, Joan Martínez Alier’s notion of "environmentalism of the poor," and Anibal Quijano’s "coloniality of power." Considering that the ecology movement in the 1960s and 1970s extended the critique of the domination of nature and human beings by industrial capitalism, and that this critique was begun by Marx, Engels, and the Frankfurt theorists, as Carolyn Merchant has pointed out, it is worth looking at the relationship between first-world capitalism and third-world colonialism through Immanual Wallerstein’s model of core and peripheral economies (Merchant 2008, 20). Globalization as the expansion of first-world capitalism into third-world countries, where resources are cheap, environmental regulations are weak, and free trade is promoted through tariff reductions, has led to characterizations of "corporate globalization as the latest stage of colonial imperialism" (ibid., 20–21). This implementation of neoliberal regulations has pushed the vast majority of people into deeper poverty on marginal lands and in urban slums. Because, as Merchant rightly asserts, unchecked economic growth depletes water resources, oil reserves, food sources, and air quality, threatening bodily health and human production, exploitation and environmental degradation in Latin America is an environmental justice problem. This position within the broader and growing field of ecocriticism entails the fulfillment of basic needs through the equitable distribution and use of natural and social resources and freedom from the effects of environmental misuse, scarcity, and pollution.

Because this paper is part of a larger conversation on the future of the humanities, it is worth addressing this issue in the context of what I just discussed. In what way can the humanities make a meaningful intervention in these environmental concerns, which have typically fallen within the province of the hard and social sciences? Whereas quantitative approaches have dominated the field—even when scholars have tried to tackle the "human dimension" of the environment—an environmental humanities approach rests on a deeper analysis of the cultural frameworks that structure understanding of our environments (Van Dooren 2012). A realm that combines nature and culture differs from one society to another as well as from one time period to another, and these constructions are a "complex social fabric" made out of traditions, customs, origins, and an "ever-changing sense of place" (Nye et al. 2013, 7). Because the problems confronted by an environmental humanities approach are interdisciplinary, they will also require new configurations of knowledge, innovative epistemologies that are informed by novel forms of thinking and interaction, and that reassess the value of both other cultures and other species.

References

Aira, César. 2001. La villa. Buenos Aires: Emecé.

Appadurai, Arjun. 1988. The Social Life of Things. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Auyero, Javier, and Débora Swistun. 2009. Flammable: Environmental Suffering in an Argentine Shantytown. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2004. Wasted Lives: Modernity and Its Outcasts. Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

Belli, Gioconda. 1996. Waslala: Memorial del futuro. Barcelona: Emecé.

Berni, Antonio. Paintings.

Castillo Berthier, Héctor. 2010. "La basura y la sociedad." In Residual: Intervenciones artísticas en la ciudad, 135–46. México D.F.: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México / Museo Universitario Contemporáneo de Arte.

Contreras Castro, Fernando. (1993) 1994. Única mirando al mar. San José, Costa Rica: Farben Grupo Editorial Norma.

Coutinho, Eduardo. 1993. Boca de lixo, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UY-4w-JQkOw&list=PLFDF37C45762F221A.

———. 1997. "O cinema documentário e a escuta sensível da alteridade." Projeto História 15: 165–71.

Davis, Mike. 2004. "Planet of Slums." New Left Review 26: 5–30.

Del Llano, Eduardo. 2000. "Greenpeace." In Nuevos narradores cubanos, edited by Michi Strausfeld, 107–118. Madrid: Siruela.

Douglas, Mary. (1966) 2002. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concept of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge.

Heffes, Gisela. 2013. Políticas de la destrucción / Poéticas de la preservación: Apuntes para una lectura (eco)crítica del medio ambiente en América Latina (Politics of Destruction / Poetics of Preservation: Notes for an [Eco]Critical Reading of the Environment in Latin America). Rosario: Beatriz Viterbo. English translation forthcoming: Bucknell University Press.

Lauria, Adriana, and Enrique Llambías. 2005. Antonio Berni [en línea]. Buenos Aires: Centro Virtual de Arte Argentino. Accessed May 5, 2016, http://www.cvaa.com.ar/02dossiers/berni/3_intro_01.php.

Livon-Grosman, Ernesto. 2006. Cartoneros. Documentary film. Trailer available on YouTube.

Marcos, Plínio. 1978. Homens de papel. São Paulo: Global Publishing.

Melosi, Martin. (1981) 2004. Garbage in the Cities: Refuse, Reform, and the Environment. Pittsburgh, PA.: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Merchant, Carolyn, ed. 2008. Ecology: Key Concepts in Critical Theory. New York: Humanity Books.

Nye, David E., Linda Rugg, James Fleming, and Robert Emmett. 2013. The Emergence of the Environmental Humanities. MISTRA. The Swedish Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research: Stockholm.

Parra, José Luis. 1958. Mis amigos los pepenadores. (La vida de un Maestro de Banquillo). México: J. Pablos.

Rathje, William L., and Cullen Murphy. 1992. Rubbish! The Archaeology of Garbage. New York: HarperCollins.

Ribeyro, Julio Ramón. 1994. "Los gallinazos sin plumas." In Cuentos completos, 21–29. Madrid: Santillana.

Shanks, Michael, David Platt, and William L. Rathje. 2004. "The Perfume of Garbage: Modernity and the Archaeological." Modernism/Modernity 11 (1): 61–83.

Van Dooren, Thom. 2012. "Science Can’t Do It Alone: The Environment Needs Humanities, Too." The Conversation, October 1. Accessed May 10, 2016, http://theconversation.com/science-cant-do-it-alone-the-environment-needs-humanities-too-9286?sg=2fe4484d-7d06-4eb5-95f3-6e5d40c5fb7e&sp=1&sr=1http://theconversation.com.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images in this work are not subject to this license.