Political theory is a very strange academic discipline.

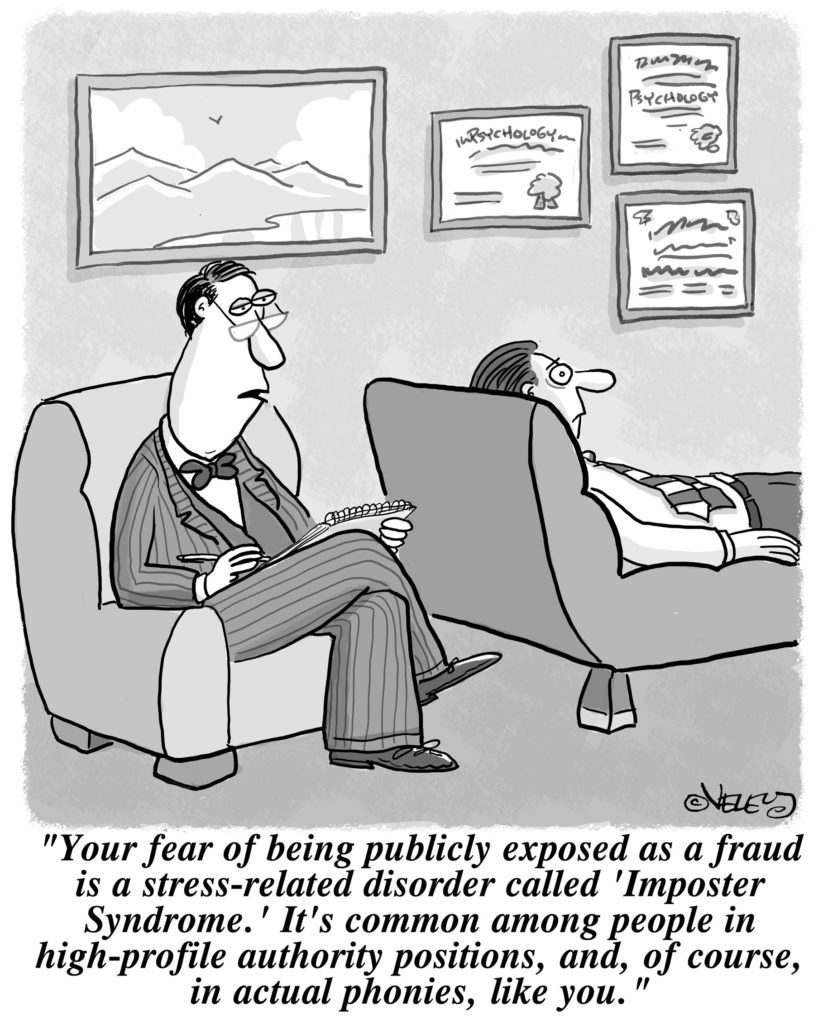

No matter where we go, political theorists can seem like impostors. Social scientists think we’re social scientists who are bad at math; philosophers think we’re philosophers who are bad at logic. To historians, the problem is that we don’t have enough patience to spend years at a time in the archives. We haven’t read enough Derrida and Deleuze to be hip in the humanities. We do what legal scholars would like to do, perhaps, if they didn’t have that pesky real world to think about.

Political theory is a very strange academic discipline. No matter where we go, political theorists can seem like impostors.

From the perspective of each discipline, I think, we must plead guilty as charged. We are, in a way, trying to do what social scientists and philosophers and historians and humanists and legal scholars are doing, and they are right—we don’t do any of those things in quite the same way that they do them. But it’s not because we’re bad at math, or logic, or because we don’t have the patience to spend years in the archives or wade through A Thousand Plateaus. Okay, maybe some of those things are true.

But really, it’s because we’re not just doing any one of those things. We’re doing all of them. Political theory is a very strange academic discipline because it’s not really a discipline at all—perhaps we could even say that it’s an anti-discipline. And in case it’s not clear, I mean that as a compliment.

At its worst, it’s a collection of the caricatures I’ve just described: pretenders, impostors, wannabes. We’ve all been to conferences. But at its best, it’s a collection of scholars who have been trained by their engagement with an incredibly rich canon of texts to think synthetically, systematically, and, if you’ll pardon the expression, bigly. Who else would have the audacity to write a history of the entire development of international law or, for that matter, the origins of modernity itself? And yet: what questions are more worthy of answers?

Political theory is a very strange academic discipline because it’s not really a discipline at all—perhaps we could even say that it’s an anti-discipline.

Back to that canon for a moment. As a white dude myself, I’m not going to lecture anyone about the importance of listening to white dudes. But I think you can accept the critiques of the canon that have been made by women, scholars of color, and indigenous scholars and try to expand and even rewrite the canon, and still appreciate the role that a canon of some kind plays in holding this field together.

Political theory, the strange, beautiful unicorn of a field that it is, is not united by a method or a set of methods, like most of the rest of political science, or history, or even analytic philosophy. It’s not really united by a circumscribed subject matter either. And don’t tell me it’s united by a concern for politics unless you can give me a definition of politics that political theorists agree on.

So what is it that everyone trained as a political theorist does? We take our comprehensive exams. No, really. We’ve all read and taught Plato and Aristotle and Machiavelli and Hobbes and Rousseau and Tocqueville and Marx and Arendt, and soon enough we’ll hopefully all have read and taught Wollstonecraft and DuBois and Fanon as well. Some of us do scholarship on those texts and some of us don’t, but that’s the common language we share. No other discipline is really like that. And it enables us to do the discipline-defying work that we do at our best.

I want political theory to get over its impostor syndrome. I want it to be an unapologetic mongrel of a discipline; part social science, part philosophy, part history, part humanities.

My aspirations for the future of political theory, then, are in one sense quite humble: I want more of the same. I want political theory to do what it already does, but to do it more fully, more openly, more proudly. I want political theory to get over its impostor syndrome. I want it to be an unapologetic mongrel of a discipline; part social science, part philosophy, part history, part humanities.

There will always be particular scholars in political theory who are more of one than the others, who engage more with social science or philosophy or history. But none of the authors we read in the canon were just political theorists; that’s what makes their texts so rich and rewarding. And the contemporary political theorists who inspire me the most are the ones who really engage seriously with all of its styles and modes. It’s because they do that, I think, that they have something uniquely valuable to contribute—not only to the discipline of political theory but also to the real political challenges of political life.

Alex Oprea was pointing out to some of us recently that the intellectual heroes of the twentieth century in Romania, where she grew up, did all of their best work from prison. And my mind went to a little bit of a dark place, as it tends to do these days. I thought: at least political theory mattered. At least someone was afraid enough of what they were thinking that they tried to suppress it; at least someone cared enough about what they said to smuggle it out, publish it, and remember it a hundred years later.

I think we’re entering an era now where political theory matters, more than it has for a while, which gives us an opportunity as well as a responsibility.

I think we’re entering an era now where political theory matters, more than it has for a while, which gives us an opportunity as well as a responsibility. There are more than enough people to blame for the situation we’re in and more than enough failures to go around. But one of those failures is ours, as political theorists, and that is the failure to communicate what democracy is about. I don’t mean that we need to write more op-eds for Vox and the Monkey Cage, although that probably doesn’t hurt. And I don’t mean that we need to go to prison—not yet anyway. What I mean is that we need to think harder about what real communication would look like.

Because political theory may be a strange academic discipline, or even an anti-discipline, but in the end it doesn’t matter where political theory fits into the academy. What matters is the role it plays, or fails to play, in sustaining a democratic society.

See also the brief essays on the future of political theory by Nora Hanagan, Michael Gillespie, Alexandra Oprea, and Chris Kennedy, which come out of the same event and are intended to be in conversation with this paper.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images in this work are not subject to this license.