A term invented by the global historian Marshall Hodgson, Islamicate is at once precise and woolly. It evokes Islam—its past, present, and future—yet the Islamicate influence exceeds any creedal or cultural limits.

A term invented by the global historian Marshall Hodgson, Islamicate is at once precise and woolly. It evokes Isla—its past, present, and future—yet the Islamicate influence exceeds any creedal or cultural limits. It reflects Muslim presence—foremost as an aesthetic taste but no less as an ethical project. Its single-line definition is best etched by Srinivas Aravamudan when he notes that Islamicate = "the hybrid trace rather than pure presence or absence of Islam" (Aravamudan 2014). And while Aravamudan’s (2014) translation of Islamicate relates to his own project to reconceptualize East–West relations by "investigating the prehistory of transchronic world literature in relation to broader contextualizations from Asia and especially the Levantine regions across the Mediterranean from Europe," my own project is to understand the inherently cosmopolitan nature of the Afro-Eurasian oikumene, not only prior to the rise of Europe but also after the colonial period of European rule throughout much of Africa and Asia, dotted with majority Muslim populations.

Both Aravamudan and I begin with Hodgson. His project is a paradox: to reinvent world history without prior prejudgments about place or time, and so to locate Islam at its center instead of at the periphery. Many have acknowledged his genius, but few have embraced his terminology, and the present paper is an effort to show how Islamicate—along with the related term, Persianate—pervade even when neither term is used. This project—to recuperate and apply Hodgsonian terminology in the service of Hodgson’s historical revisionism—can be best etched as an inquiry into Islamicate political aesthetics. It involves both power and beauty, politics and art, with equal emphasis on the pragmatic and the ideal, yet without boundaries either temporal or spatial.

His project is a paradox: to reinvent world history without prior prejudgments about place or time, and so to locate Islam at its center instead of at the periphery.

Marshall Hodgson was a genius denied, author of The Venture of Islam, the most radical rethinking of Islam in world history since Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406).[1] Islamicate and Persianate are two of several terms coined by Hodgson ca. 1965 to explain the force and subtlety of cultural practices in Islamic civilization. They are scarcely found either in academic or popular venues dealing with art and architecture from the Muslim world. Why?

Instead of accepting this gap between Hodgson’s influence and contemporary use, or neglect, of his terminology, I ask the further question: Can someone produce an art book that is Islamicate/Persianate in substance but not in name? To make the case, I examine two museum catalogues and one coffee-table book. All three are Islamicate/Persianate in tone, evidence, and argument, yet none of the editors mentions by name either Marshall Hodgson as author or Islamicate/Persianate as categories of analysis. In what follows, chiefly by looking at a number of artistic productions featured in these luxuriant volumes, I want to ask: How do we wrestle with this aporia between Hodgson’s ethical revisionism—he even subtitled his magnum opus: Conscience and History and in a World Civilization—and his contemporary legacy, marked by nominal recognition of his stature but also continuous neglect of his plea for parity across time and space? I want to suggest that there are benefits to retrieving the influence of Hodgson’s terminology in general but especially in relation to political aesthetics, the topic of this intervention.

How do we wrestle with this aporia between Hodgson’s ethical revisionism and his contemporary legacy, marked by nominal recognition of his stature but also continuous neglect of his plea for parity across time and space?

There are three sites of tacit Islamicate political aesthetics that I have selected for my intervention on behalf of Hodgson and his revisionist project:

- Pre-modern, from the three gunpowder empires, artworks displayed in an Istanbul museum

- Modern, from Persianate artists in a New York City museum

- Protest, from Iranian artists in the Islamic Republic of Iran, as reviewed and analyzed by two U.S.-based academics

I want to argue that there is neither a single place nor a single worldview that excludes Hodgsonian terminology. He begins where we must begin, with a consistent, transnational, global recognition that the traditional terms "Muslim" and "Islamic" are inadequate. Too imprecise and subject to misunderstanding, they can no longer be applied to works of art that come from either places or actors of the Afro-Eurasian oikumene marked as majority Muslim, and instead one must substitute for them "Islamicate."

Consider Islamicate art from the 1500s on. It requires recognizing the Timurid origins of embedded cosmopolitanism. There were urban trade networks that shaped and reshaped aesthetic norms and cultural production throughout the Afro-Eurasian oikumene (another Hodgsonian neologism to explain the interconnectedness of the known world prior to the 16th century and discovery of the Americas). The book that traces political aestheticism from this period is titled, Three Capitals of Islamic Art. It features objects from the Louvre collection in Paris on display in Istanbul at Sakıp Sabancı Müzesi in 2008, and it highlights the artistic production of three metropolitan sites in the pre-modern Muslim world: Istanbul, Isfahan, and Delhi.

All three capital cities—Istanbul, Isfahan, and Delhi—were influenced by Persian but also Chinese and Central Asian motifs. Yet only Hodgson hints at their collective connection to Timur/Tamerlane (d.1405), a Chaghatai Turk with Mongol aspirations. Hodgson renames the Mughal dynasty; it becomes Indo-Timurid, that is, Timur grounded in India, since Babur, its founder, was the great-great-great grandson of Tamerlane. Proud of his ancestry, Babur, like Timur, had no Mongol blood, only Mongol attachment.

What makes all three cities Islamicate? Because they are not just linked to Timur but also to a certain sensibility. All three are capital cities in post-Timurid empires: in addition to kingship and sainthood, they embrace a public celebratory tone, at once aesthetic and ethical, in everyday life. To quote from the catalogue: "The three Islamic empires of this exhibition, Ottoman (1299–1923), Safavid (1501–1722), and Mughal (1526–1858), shared a common cultural heritage forged by the former Islamic dynasties of the geographic region of pre-modern Greater Iran (parts of Transoxiana, Afghanistan, Iran, and Iraq), the last propagators of which are the Timurids (1396–1510) . . . (and then modern notions of national identity intrude, so that) modern sensibility accepts the Safavids as the natural heirs of the former dynasties of Iran (the modern state) for territorial reasons, and that the Mughals, whose dynastic founder (Babur) was the grandson of Timur himself, had close family ties to Timur" (Istanbul, Isfahan, Delhi 2008, 39). Yet the catalogue author goes on to explain that the Ottoman case, absent territorial or genealogical ties, is harder to make, except on aesthetic grounds. The exception is crucial for our argument, since it is aesthetics, or better political aesthetics, that explain not just the common affinity of the three capitals but also their relationship to nature, to animal and aviary life, and above all to poetry.

Let us begin with the cover of the catalogue. We might describe the theme as: Birds do it, that is, the cover image of birds displays the affective, performative attachment to nature and avifauna in art that permeates all three empires and their capital cities:

Sabanic Catalogue, Istanbul, Isfahan, Delhi: Three Capitals of Islamic Art (Istanbul, February 2008). Title page.

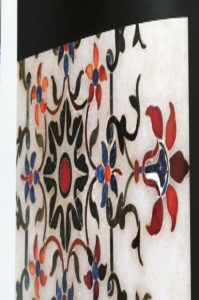

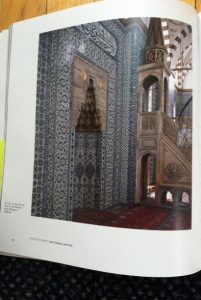

A key example, also provided in the catalogue, is the Rustam Pasha mosque in Istanbul:

The Rustem Pasha mosque, Istanbul (16th century). In Istanbul, Isfahan, Delhi.

It is impossible to ignore the patterns; not only are they symmetrically aligned but they also display blue, white, and red floral patterns, with tulips abounding in its entrance.

It is but a small step from this mosque pattern to a much smaller relic of the same past: a 16th-century Iznik plate. Compare the patterns here with those of the mosque tiles. Again tulips triumph, as they do in both Turkey and Iran from the pre-modern to the modern to the contemporary period:

Iznik plate, 16th century: tulips triumph, in both Turkey and Iran. In Istanbul, Isfahan, Delhi.

But the best way to describe this diffuse and popular pattern is not as Muslim, though there are Muslim consumers, nor as Islamic, though many see an engagement with Qur’anic themes of nature and balance. But it is instead Islamicate because it permeates all levels of society regardless of class, language, or religion, and it also extends from Syria to Turkey to China. "The local production of tiles," as the catalogue explains, "were known in Damascus as ‘qishani’ derived from the name of the Iranian city of Kashan (because they were linked to that site), until the nineteenth century." Yet the historical/geographical origins are deeper still, for the Damascene color palette . . . "is itself a color scheme already found in the Mamluk era, despite the predominance in blue-white contrasts in the concern for imitating Chinese Yuan and Ming porcelain." Indeed, the primary difference between Iznik plates of the late 15th century and earlier Damascene tiles is that the technology of the former "brought the quality of Iznik production on a par with that of Chinese porcelain and contributed to their international renown, which continues till today." [2]

What needs to be stressed here is the huge trans-regional network of both production and aesthetic taste that originated from the Yuan (Mongol) period and persisted through Timur (a Chaghatai Turk as well as a Mongol), and shaped the public as well as private taste of those who were its most avid consumers. And nowhere is this arc of influence—at once territorially and culturally capacious—more evident than in poetry. Not just art objects but also verses can/should be described as Islamicate and, to the extent that it echoed the influence of Greater Iran, Persianate. Here are Islamicate/Persianate lyrics linking Iran to Syria to Turkey in a single tile panel. That is, they display Turko-Arab-Persian taste, with Mongol-Central Asian antecedents, in the form of Syrian Ottoman Persian(ate) tile. The panel occupied domestic space in 16th century Damascus:

Syrian Ottoman Persian(ate) tile, domestic space, also 16th century. In Istanbul, Isfahan, Delhi.

Here is how it is described in the catalogue: "the panel displays the final beyt of a ghazal by the famous poet Hafiz, a native of the city of Shiraz: ‘The chant of Thy assembly swells the heavens, now that the poem of Hafiz of mellifluous tongue is Thy song.’" Yet, the cataloguer goes on to explain, "this panel does not come from Iran, but in all likelihood from Syria." And what are its aesthetic characteristics? "In the floriated frieze framing the inscription can be seen the bright chrome green so characteristic of Damascence production in the Ottoman era, combined with cobalt blue and turquoise" (and, one might also add, with a dominant blue-white contrast harking back to the rivalry/emulation of Chinese tiles) (Istanbul, Isfahan, Delhi 2008, 153).

A similar color patterning can be detected in Mughal India, in a no less celebrated site than the Taj Mahal.

- The royal touch: a Taj Mahal tile with 48 different stones, from where? In Istanbul, Isfahan, Delhi.

- Close up of Taj Mahal tile. In Istanbul, Isfahan, Delhi.

We might call this tile "the supreme royal touch," for here is a Taj Mahal tile with no fewer than 48 different stones. But from where? At the height of Mughal imperial art we are told that "stoneworkers set in marble or sandstone thin sections of hard or semi-hard stones that had been cut with the greatest of care and fashioned in the shape of tendrils and floral arabesques. . . The hard stones used in the decoration of the Taj Mahal, as well as in palaces and imperial buildings all over India and in the surrounding regions, included yellow amber from Burma, lapis-lazuli from Afghanistan, nephrite from Chinese Turkestan, and carnelian, agate, amethyst, jasper, and green beryl from different parts of India" (Istanbul, Isfahan, Delhi 2008, 297). In short, the continuous connection with China, both in the styles imagined and the elements used, shows an Islamicate pattern: produced under Muslim imperial rule, but embodying and projecting aesthetic values that preceded and also exceeded creedal or ritual loyalty to Islam qua religion.

While too few art historians have reflected on the Islamicate nature of these traces from the imperial past of the Afro-Eurasian oikumene, Judith Ernst provides a welcome exception. Here is her depiction of the Islamicate nature of high imperial art in the age of post-Timurid empires. In introducing her essay on "The Problem of Islamic Art," she observes that the challenge is "to accommodate an understanding of religion that includes culture," and to that end, "scholars have adapted the term ‘Islamicate’, suggesting that (what is termed) ‘Islamic’ may be related to actors of interests (deemed Muslim) but is expressed by or for a non-Islamic audience or an audience for which the fine line between Islamic and other loyalties is shaded" (Ernst 2003).

In short, Ernst’s expanded definition of Islamicate mirrors what Srinivas Aravamudan had described elegantly as: "the hybrid trace rather than pure presence or absence of Islam." The importance of Islamicate was earlier stressed in a 2000 book from a 1995 conference, which I co-edited with David Gilmartin. It was titled, Beyond Turk and Hindu: Rethinking Religious Identities in Islamicate South Asia. Here is the relevant quote:

"Coined by Marshall Hodgson in the mid-60s, Islamicate denotes the moral values and cultural forms that spread through the world system of Muslim trade and power in the centuries following the rise of Islamic polities. . . . Although Muslims did not make this distinction, the distinction between Islamicate and Islamic/Muslim is extremely useful for us. . . . Especially in South Asia the term Islamicate captures the civilizational dynamic for the framing of inclusive religious identities, not least in architectural tastes and choices, as analyzed by Catherine Asher in her chapter, ‘Mapping Hindu-Muslim Identities through the Architecture of Shahjahanabad and Jaipur’" (Gilmartin and Lawrence 2000, 3, 10, 121–148).

And so, it was known that Islamicate pervaded the sense of (re)discovery: (1) about the interconnected cultures of the great Muslim empires but also (2) regarding the accent on political aesthetics as both Islamicate and Persianate, drawing on a large repertoire of styles, resources, and practices, with the hybrid trace of Islam but not its announced presence or rejected absence in the actual work or the intended audiences. And yet we find in 2006, less than a decade ago and more than three decades after Hodgson’s The Venture of Islam was published, a bountiful catalogue at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City that totally overlooks both Hodgson’s work and his nomenclature for rethinking Muslim art as Islamicate.

Here is how the editor, Fereshteh Daftari, addresses the hybrid traces of her contributing artists. Citing noted Harvard–MIT art historian Oleg Grabar, she observes that "the word ‘Islamic’ does not refer to the art of a particular religion." What does that mean? According to Grabar, it means precisely that "works of art demonstrably made by and for non-Muslims can appropriately be studied as works of Islamic art." But what of non-Muslim art embraced by Muslims or made for Muslims? Clearly there is a gap here between practice and vocabulary. We have seen it richly illustrated above in the Sabanci museum catalogue: Islamic art is genuinely Islamicate, crossing boundaries of time and space in a manner that evokes Muslim sensibilities but without creedal or liturgical conformity. Both Muslims and non-Muslims are involved in production as well as consumption. Instead of making an easeful connection to Hodgson’s political aesthetics and to the term Islamicate, however, Daftari goes on to say:

"In this polarized moment (evoking in 2006 the horror of 11 September 2001), the term (Islamic) may seem too tightly tied to the religion of Islam to allow any secular meaning, but artists from the Islamic world are by no means all practicing Muslims or for that matter Muslims at all. The art in Without Boundary rarely refers directly to personal religious beliefs, but a sense of spirituality does appear, not necessarily anchored in any one creed" (Daftari 2006, 22).

The shortfall of this statement is its timing: not its publication in 2006, but rather its citation of Grabar’s work from 1973 when during the next year, 1974, Hodgson’s The Venture of Islam appeared in print, providing vocabulary and argument as well as evidence and insight that were lacking in Grabar, despite his other, notable achievements. Hodgson provides insight into the cosmopolitan aesthetic of several artists, eliding Muslim to non-Muslim elements and influences, all featured in Without Boundary.

Consider Berkeley educated, Iranian-American Shirin Neshat’s works: no. 1–untitled. Poet: Forough Farrokhzad; and no. 2–Speechless. Poet: Tahereh Saffarzadeh:

- Without Boundary: Seventeen Ways of Looking by Fereshteh Daftari (2006). Without boundary but also without Islamicate.

- Untitled work by Shirin Neshat, Berkeley educated, Iranian American. Poet: Forough Farrokhzad. In Daftari.

- Speechless by Shirin Neshat (1996). Poet: Tahereh Saffarzadeh. In Daftari.

Neshat had left Iran in 1974, then returned 16 years later in 1990. Both the above images, like others she has produced, feature women embodying contradictions, at once visual and lyrical, reflected in gestures but also in poetry. The first is untitled, yet it features both a religious invocation on the outer palm, and then inscription on the fingers from poet Forough Farrokhzad. The woman may be trying to speak or entreating her viewer to remain silent. The contradictions abound here, as they do in the second image, titled Speechless. Part of a series called Women of Allah, begun in 1993, it projects a woman who wears a gun barrel in place of earrings, her face veiled not with cloth but with script: "a eulogy to martyrdom in the name of Islam, quoted from the writings of another woman poet, Tahereh Saffarzadeh" (Daftari 2006, 13). Islamicate tones pervade, unnamed but still evident.

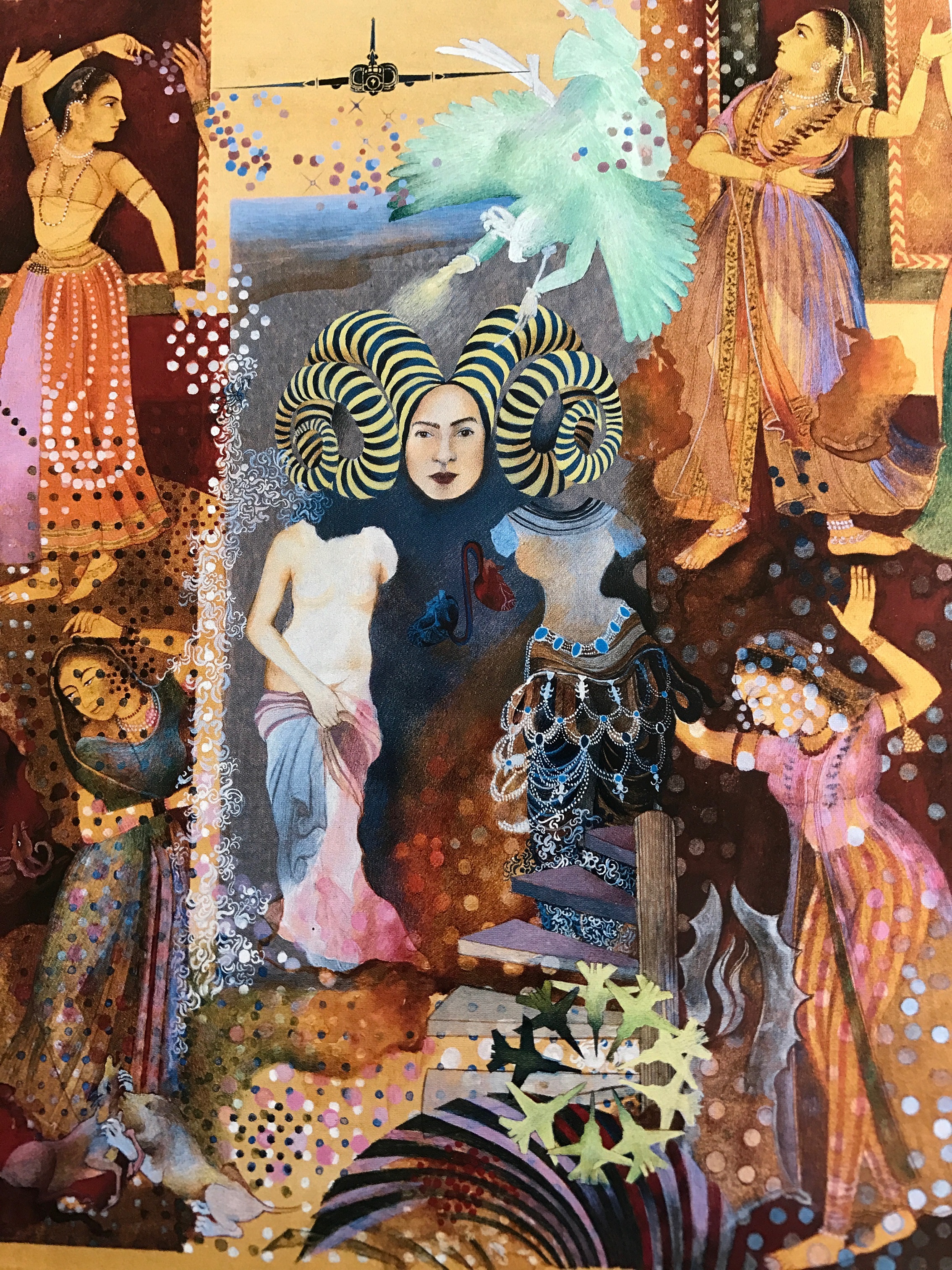

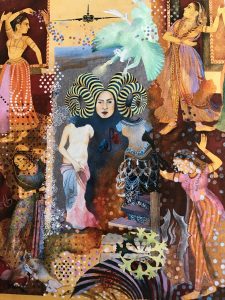

Pleasure Pillars by Shahzia Sikander (2001), RISD graduate, Pakistani-US artist and Islamicate cosmopolitan. In Daftari.

And also in this same catalogue are paintings from Shahzia Sikander, RISD graduate, Pakistani-U.S. artist, and Islamicate cosmopolitan. In Pleasure Pillars, Sikander "embraces heterogeneity. Dancing figures drawn from Mughal miniatures, a classical Venus matched by a figure of the Hindu goddess Devi, a self-portrait with spiraling horns, the high-tech war machinery of a modern fighter plane, and battling animals plucked from miniatures of Iran’s Safavid period form the elements of a narrative without a story line." These layers of ideas create open-ended possibilities, traceable to semiotics and post-Structuralist theory. Like the German painter, Sigmar Polke, whom she admires and whose work she studied, Sikander attempts to layer paint with narrative in order to destabilize fixed meanings and create new vistas (Daftari 2006, 14–15).

In short, Sikander, like Neshat, provides multiple hybrid traces, connecting diverse traditions but always with a central political aesthetic intent: to connect poetry with nature and use both to reinforce a liberatory message for all persons, but especially women, whether Persian or Greek, Muslim or pagan. It is, in short, an Islamicate manifesto in visual garb.

In the examples that follow, cosmopolitan, far from being a marker of upper class or royal status, defines an Islamicate aesthetic that evokes and performs protest, nowhere more so than with the overthrow of the Pahlavi Shah (1979) and the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran (1979– ).

Two senior scholars of Iran produced a magnificent coffee-table book in 1999. Staging a Revolution, by Peter Chelkowski and Hamid Dabashi, surveys the aesthetic practices of Iranian revolutionaries during the preceding two decades.

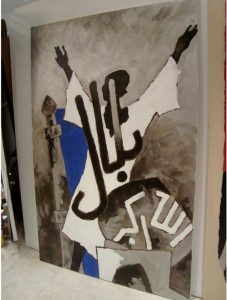

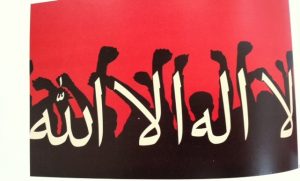

Despite the absence of Hodgson’s key words in both the title and the text, the content of this sumptuous book dramatically illustrates both Persianate and Islamicate themes, whether with images of tulips marking stamps and posters (Chelkowski and Dabashi 1999, 41) or refashioning the shahada as a calligraphic protest at once Arabo-Persian but also Polish, modeled after the Solidarity logo in Poland:

Making the shahada a calligraphic protest (Arabo-Persian) but also Polish, modeled after Solidarity logo in Poland. In Chelkowski and Dabashi.

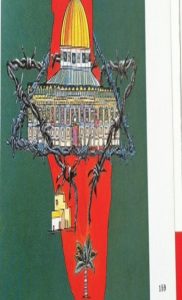

From Shazia Sikander’s spiraling horns to the "wormy" Shah, we confront nature writ large—invertebrate, winged, floral, and human as also edible, geographic, calligraphic, and urban elements. Here in protest, they illustrate the durable flexibility of Persianate-modern and Islamicate themes:

From Shazia Sikander’s spiraling horns to the "wormy" Shah: nature write large, invertebrate, winged, floral, and human, also edible, geographic, calligraphic, and urban elements, a.ka. Persianate-modern, or Islamicate. In Chelkowski and Dabashi.

The link is also architectural, recurrently to the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem,[3] the Star of David depicted as barbed wire incarcerating history and geography yet also open to liberation at the bottom through a solitary palm tree:

Dome of the Rock barb-wired with the Star of David: architectural, geographic, and symbolic, at once incarcerating and liberatory. In Chelkowski and Dabashi.

There are, to be sure, the dedicated few who do support and expand the notion of Persianate. The Association for the Study of Persianate Societies, founded in 1996, has held biennial meetings since 2002 and published a journal since 2008, both of which promote its aims, namely, to explore and analyze "the culture and civilization of the geographical area where Persian has historically been the dominant language or a major cultural force, encompassing Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan, as well as the Caucasus, Central Asia, the Indian Subcontinent, and parts of the former Ottoman Empire." [4]

And despite the pervasive absence of Persianate/Islamicate in museum catalogues and coffee-table books, both terms do find a place from time to time in high critical discourse, especially on the legacy of Indo-Persianate poetry and art. A recent example is Nauman Naqvi, an American-trained Pakistani anthropologist. In "Acts of Ascesis, Scenes of Poesis" (Naqvi 2012), he analyzes the Pakistani poet–painter Sadequain, foregrounding Islamicate elements, albeit in densely argued endnotes, such as the following:

The primacy of poesis in Islam is, to begin with, given linguistically in Arabic in the very word for poesy, shi‘r (in Hindi/Urdu, sher). A very moving testimony in this regard is that of the Tunisian thinker, Abdelwahab Meddeb: "The legacy of Islam consists in the profusion and intensity of its body of spiritual texts. This legacy owes as much to the ardor and intensity of its poetic and lyrical sayings as to the exalted tenor of its speculations." Meddeb, Islam and its Discontents (2003), p. 42 [i.e., it is implicitly Islamicate not Islamic].[5]

In other words, what Naqvi, a Pakistani-American critic, is arguing echoes the assertion of Meddeb, a Tunisian-French critic, to wit, that Islam cannot be reduced to religious/spiritual texts, but instead evokes a sensibility—what I’ve insistently qualified as a political aesthetic sensibility—that is marked, above all, by "the ardor and intensity of its poetic and lyrical sayings," never more so than when they are combined in another artistic genre, whether photography and painting in the modern era or tile and architecture in the pre-modern era.

This overview only hints at the aporias of mimesis/poesis, where brilliant scholars echo but do not name, or name but do not expand, the Islamicate. There are, however, other signs of new life for these now old, if also seldom invoked, categories. I would like to close by illustrating two explicit trajectories of Islamicate aesthetics: (1) in the future work of a young Bengali-American art historian, and (2) in the analysis of a legendary Yemeni-Indian-Qatari artist.

What is crucial here, as elsewhere, is the defining function of hyphens: they make connections that are often occluded, erasing history, confusing precedents, deflecting memories and, above all, dimming vistas of the future.

What is crucial here, as elsewhere, is the defining function of hyphens: they make connections that are often occluded, erasing history, confusing precedents, deflecting memories and, above all, dimming vistas of the future. Already marked as cosmopolitan are two artists, one as "Bengali-American," the other as "Yemeni-Indian-Qatari." But apart from the hyphens, what makes both artists also Islamicate cosmopolitans?

The first, a Bengali-American, is Sugata Ray. Here he is focusing on a single object, a Rajasthani Krishna-Radha shrine that is now part of Doris Duke’s collection at Shangri-La. See https://vimeo.com/73413831.In this brief clip, there is no mention of Islamicate, yet the "Muslim" object comes from Jaipur, the same Hindu temples of Jaipur that were analyzed by Catherine Asher in her contribution to Beyond Turk and Hindu (Gilmartin and Lawrence 2000). Can one say that it is perhaps more than mere coincidence that Ray is a PhD graduate from Minnesota where one of his teachers was Catherine Asher?

This lapse in genealogical attribution during the Shangri-La lecture will be remedied, fortunately, in a future project from this creative art historian. It is described on Ray’s webpage (http://www.sugataray.com). There, Sugata Ray promises: "engagement with the artistic cultures in medieval South and Central Asia in order to reconfigure the cosmopolitan aesthetics of the Islamicate through geospatial registers." In short, Sugata Ray is himself a cosmopolitan transfixed with cosmopolitan Islamicate elements from the pre-modern Afro-Eurasian oikoumene.

Yet it is not just in the past but also in the present that one needs to recuperate and apply the qualifier "Islamicate," above all, to art that emerges from the Afro-Eurasian oikumene, often with a tilt toward Euro-American influence. No stronger case could be made for these "hybrid trace(s) rather than pure presence or absence of Islam," as defined by Srinivas Aravamudan, than with the late Indian-Qatari painter, M. F. Husain, an Islamicate cosmopolitan mining contemporary idioms from the Indian Ocean.

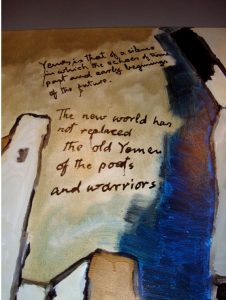

- Staging a Revolution: The Art of Persuasion in the Islamic Republic of Iran by Peter Chelkowski and Hamid Dabashi (1999). Absent Hodgson, Islamicate or Persianate in title or text, yet present in practice at multiple levels.

- Nostalgia, recuperation, or both? Time collapses in the Indian Ocean Islamicate world writ large by M. F. Husain. In Chelkowski and Dabashi.

- Bilal/Obama (2008). No title or text but still an Islamicate vision across time. In Chelkowski and Dabashi.

- Iconic painting by M.F. Husain: Bharat Mata and the Dhow. In Chelkowski and Dabashi.

- M.F. Husain: Call of Yemen, Museum of Contemporary Arab Art, Doha. In Chelkowski and Dabashi.

Sumathi Ramaswamy, more than any other contemporary scholar, has laid bare the contributions and contradictions of Husain’s work across many divides—historical, cultural, national, and artistic. In a volume she edited, David Gilmartin, with Barbara Metcalf, have indicated how multiple civilizational frames are present in this iconic image of Husain. Among them the dhow is "a sign of India’s powerful links to an Islamicate, Indian ocean civilization" (Ramaswamy 2010, 71).

And the place of maritime reconnection for Husain is his ancestral home of Yemen, with memories also of Ethiopia.

Integral to Husain’s imagination was bringing together past and present, conjoining incongruous moments and actors in ways that seem both fantastic and farcical, irreverent as well as implausible, yet suffused with joy and evoking celebration. The Bilal-Obama connection was inspired by the 2008 U.S. presidential election. Husain stayed up late to listen to the results in Doha. He was so elated that he could not sleep (at age 93), and so he busied himself with painting Bilal, one of the first converts to Islam— an Ethiopian.

The phrase Allahu Akbar looms large at the bottom, with the name BILAL written across the central figure with upraised arms. One has to know the painter’s story of its inspiration to conclude that Obama is here projected as the modern-day equivalent of Bilal. "It took America two-hundred years," quipped Husain, "to do what Islam did in less than ten years: make a black man its major icon to the outside world" (Lawrence 2013).

Bilal was, of course, not Muhammad; he was only the leader of ritual prayer, not of the entire Muslim community. Still, the comparison reflects Husain’s ability to cross religion and politics, enriching one by contact with the other, while also denying either ultimate authority over the individual. It also marks him as an Islamicate cosmopolitan, at once non-religious yet touched by the tones of Islam in his art, as in his life.

Summary Conclusion

What links Islamicate to Persianate to cosmopolitan? The ubiquitous hyphen. The range of data presented above moves across continents and oceans, spaces and ages, yet it has a single, recurrent goal: to clarify the connections that indicate an embedded cosmopolitanism throughout parts of Asia—East and West, Central and South, as well as the Indian Ocean. Far from random or incidental, they are recurrent and evocative. To understand their significance, they must be located within an historical frame that is at once political and aesthetic, resolutely Islamic yet materially rather than creedally defined, often Persianate, and always Islamicate. Despite their frequent absence in popular as also academic analyses of Islamicate culture, multiple locations and experiences, memories and genealogies must be foregrounded in art as in architecture, in street posters as well as in museums. The hyphen pervades; the hyphen endures.

Notes

- For more on Hodgson and his legacy, see my recent overview in an Op Ed for the LA Review of Books: https://islamicommentary.org/2014/11/genius-denied-and-reclaimed-a-40-year-retrospect-on-marshall-g-s-hodgsons-the-venture-of-islam-by-bruce-lawrence.

- I am grateful to Christianne Gruber for two further references to Chinese porcelain and its impact on Islamicate art (Golombek 1996; Kadoi 2009).

- Chelkowski and Dabashi (1999, 203–208) also provide several other vivid images of the Dome of the Rock created since 1979, whether on currency, coins, stamps, posters, or in a public square (Palestine Square) in downtown Tehran.

- Quoted from Arjomand (2008). The editor, a distinguished Iranian-American sociologist, does give Hodgson credit for coining Persianate in the inaugural issue. "The term Persianate was coined by Marshall Hodgson in The Venture of Islam (1974) to describe a major component of the Islamic civilization." Persian, according to Hodgson, "was to form the chief model for the rise of still other languages to the literary level. Gradually, a third ‘classical’ tongue emerged, Turkish, whose literature was based on the Persian tradition. . . . Most of the more local languages of high culture that later emerged among Muslims likewise depended upon Persian [Urdu would be a prime example]. . . . We may call these traditions, carried in Persian or reflecting Persian inspiration, ‘Persianate’ by extension" (Hodgson 1974, 2, 293) [cited from Arjomand 2008, 3]. Welcome as is this initiative, it is still too recent, its membership and readership too limited, to change the general attitude—academic and popular—that reduces Persian to present-day Iran and denies the value of Islamicate as a cultural marker.

- Naqvi (2012), in the very next endnote (no. 8), does allude to "the intimacy of mimesis and poiesis in the Islamicate, and the primacy of the latter over the former," and signals two other books where more on their relationship can be found. These books are by Gregory Minissale (2009) and Michael A. Barry (2005). While Minissale delves deeply into the mindset of Mughal painters, nowhere does he touch on Islamicate or Persianate categories in analyzing Mughal aesthetic consciousness. Similarly, Barry provides a brilliant exposition of the most heralded master of Persian miniature art, Bihzad, linking art to poetry but without the Persianate/Islamicate connections that might have made his analysis resonate with Hodgson’s global vision of history.

References

Aravamudan, Srinivas. 2014. "East-West Fiction as World Literature: The Hayy Problem Reconfigured." Eighteenth-Century Studies 47 (2): 198.

Arjomand, Said Amir, ed. 2008. "Defining Persianate Studies." Journal of Persianate Studies 1 (1): 3.

Barry, Michael A. 2005. Figurative Art in Medieval Islam: And the Riddle of Bihzad of Herat (1465–1535). Paris: Flammarion.

Chelkowski, Peter, and Hamid Dabashi. 1999. Staging a Revolution: The Art of Persuasian in the Islamic Republic of Iran. New York: New York University Press.

Daftari, Fereshteh, ed. 2006. Without Boundary: Seventeen Ways of Looking. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

Ernst, Judith. 2003. "The Problem of Islamic Art." In Muslim Networks from Hajj to Hip-Hop, edited by Miriam Cooke and Bruce B. Lawrence, 107. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Gilmartin, David, and Bruce B. Lawrence, eds. 2000. Beyond Turk and Hindu: Rethinking Religious Identities in Islamicate South Asia. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. 3, 10, 121–148.

Golombek, Lisa. 1996. Tamerlane’s Tableware: A New Approach to the Chinoiserie Ceramics of Fifteenth- And Sixteenth-Century Iran. Cosa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers.

Hodgson, Marshall G. S. 1974. The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization. 3 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Istanbul, Isfahan, Delhi: Three Capitals of Islamic Art, Masterpieces from the Louvre Collection. 2008. Istanbul: Sakip Sabanci Muzesi.

Kadoi, Yuka. 2009. Islamic Chinoiserie: The Art of Mongol Iran. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Lawrence, Bruce B. 2013. "‘All Distinctions Are Political, Artificial’: The Fuzzy Logic of M. F. Husain." Common Knowledge 19 (2): 274.

Minisaale, Gregory. 2009. Images of Thought: Visuality in Islamic India 1550–1750. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Naqvi, Nauman. 2012. "Acts of Askesis, Scenes of Poiesis: The Dramatic Phenomenology of Another Violence in a Muslim Painter-Poet." Diacritics 40 (Summer 2): 67.

Ramaswamy, Sumathi, ed. 2010. Barefoot across the Nation: Maqbool Fida Husain and the Idea of India. New York: Routledge, 2010.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License